You are here: Home1 / Latest News2 / Recognizing the 90th Anniversary of the Civilian Conservation Corps

Did you know April 2023 marks 90 years since the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC)?

The Corps Network’s membership is comprised of nearly 150 Corps programs across the United States. These organizations annually engage more than 20,000 young adults in service projects and job training focused on conservation and community improvement. Corps serve different populations and do different work from one community to the next: more rural programs might build wilderness trails and treat wildfire fuels, while Corps in cities might weatherize homes and manage the urban tree canopy. No matter their focus, all of today’s Corps trace their roots back to the Civilian Conservation Corps.

On the 90th anniversary of the original CCC, we celebrate all that Corps have accomplished and look to the future. We at The Corps Network believe the realities of climate change make it increasingly important that our leaders invest in a revived, justice-centered CCC for the 21st century.

On March 21, 1933, during his first 100 days in office, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the idea of the CCC to Congress. This was during the Great Depression and many people struggled to find work to support their families. Roosevelt called to recruit thousands of unemployed young men and send them to work against the destruction and erosion of America’s natural resources. As FDR said, “I propose to create a Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in simple work … more important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work.”

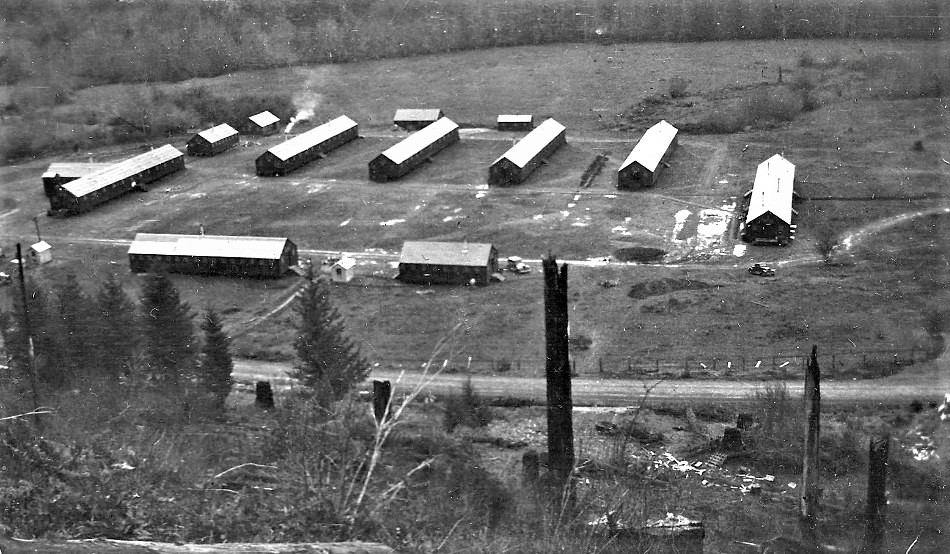

On April 5, just weeks after going to Congress, FDR signed the Emergency Conservation Work Act, creating the CCC. By April 17, the first CCC camp – Camp Roosevelt – was in operation near Luray, VA. CCC camps were overseen by the Army and would each house about 200 participants.

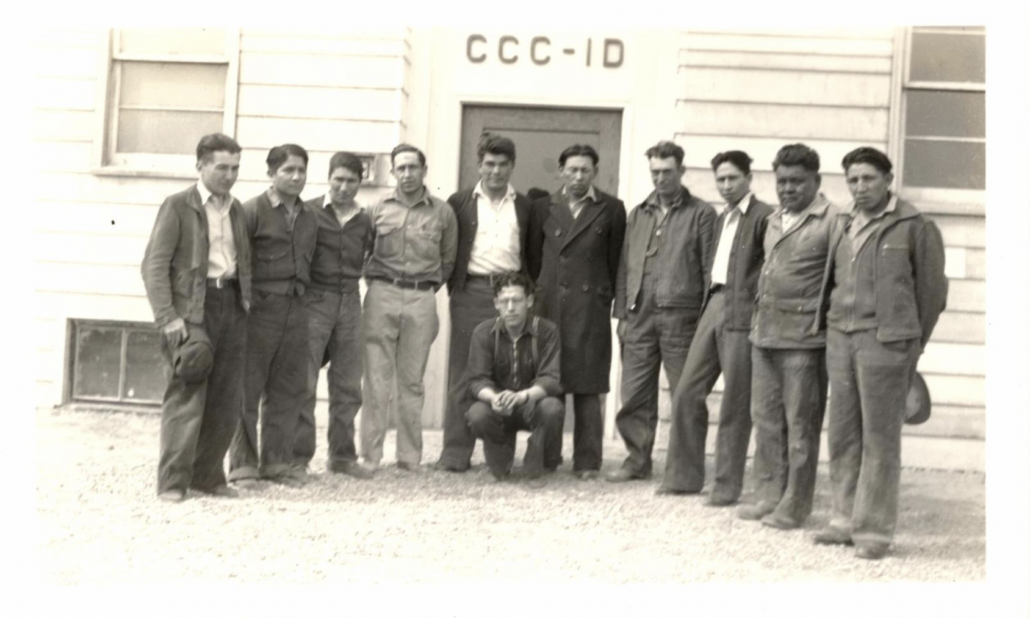

CCC enrollees had to be single and unemployed men aged 18-25 with families on government relief. Not long after the start of the CCC, the government launched a parallel program – the CCC Indian Division – which was operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs on Tribal lands. The CCCID allowed Native men who were older and married; the average age was 34. There were also separate camps operated by the Army for unemployed WWI veterans.

Most CCC participants enrolled for six months and worked a 40-hour week for $30 per month. The government sent $25 a month home to the workers’ family. By July 1, 1933, there were 275,000 enrollees and 10,000 supervisory personnel in 1,468 camps. Enrollees received good food, education, uniforms, shelter, and medical care. It was the fastest large-scale mobilization of men in U.S. history.

CCC camps operated across all 48 states, as well as the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands (St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix). Unfortunately, the CCC was not equal to all: there were no opportunities for women (beyond a short-lived “she-she-she” initiative) and the program operated during the era of Jim Crow. While some CCC camps were integrated, the program placed most Black enrollees at segregated camps that often did harder, less desirable work. Black CCC members had few opportunities for upward mobility or leadership, and enrollment numbers were capped. The more than 200,000 Black men who ultimately served in the CCC faced racist policies and challenging conditions, but they worked to support their families and played a critical role in shaping our parks. We honor their service.

The CCC left a lasting impact on our country’s landscape. Roosevelt’s “Tree Army” planted more than three billion trees on land made barren from fires, erosion, intensive agriculture, or logging. In fact, the CCC was responsible for over half the reforestation, public and private, in the nation’s history. Enrollees constructed trails and shelters in more than 800 parks nationwide. The CCC helped shape the modern national and state park systems we use today, building paths and structures that visitors can still enjoy. The CCC developed 94 national park sites, including national parks, monuments, recreation areas, and historic sites.

Just under a decade after its creation, the CCC disbanded in 1942 due largely to increased employment opportunities, decreased funding, and the need for soldiers to serve in World War II.

Learn more about the CCC from these blogs from our archive:

The model of the CCC was revived in 1957 when the Student Conservation Association (SCA) placed its first college students as volunteers in national parks and forests.

Just over a decade later, the SCA model was used as the basis for legislation that created the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC). At its height during the mid-1970s, the YCC enrolled some 32,000 young people each summer in programs operated by the Departments of Interior and Agriculture, as well as by states.

Late in the 1970s, an even larger federal program was launched, the Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC), which provided young people with year-round conservation-related employment and education opportunities.

Both the YCC and the YACC were virtually eliminated in 1981 due to federal budget cuts. By that time, however, the value of Corps had been proven and many states started to support these programs directly. California became the first when Governor Jerry Brown launched the California Conservation Corps in 1976. By the first half of the 1980s, state-operated Corps could be found in Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin.

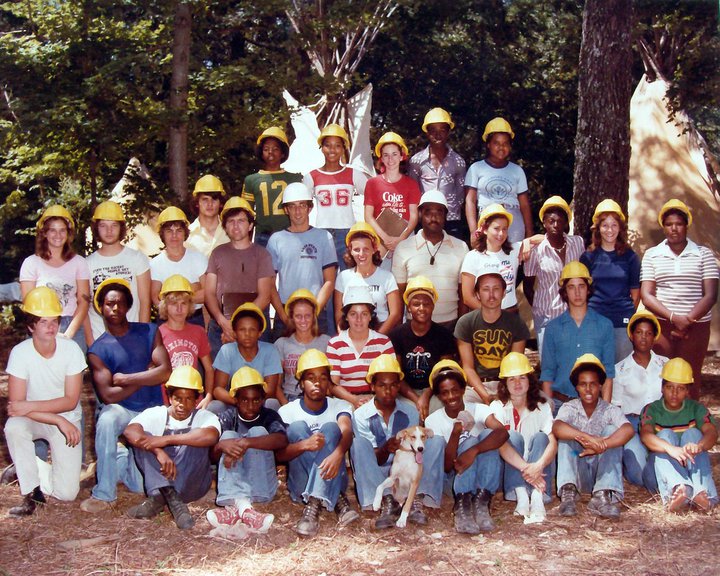

Corps work has evolved greatly over the years to meet changing needs. While many Corps do work similar to the original CCC – like planting trees, digging new trails, and fighting invasive species – there are now Corps that install solar panels, operate recycling programs, manage urban farms, create green stormwater infrastructure, and more.

Contemporary Corps also look more like America. More than 40 percent of enrollees identify as a person of color and more than 40 percent identify as female. An increasing number of Corps operate “affinity crews” that seek to provide safe spaces for underrepresented communities in the outdoors to serve and learn alongside peers with whom they share similar life experiences and identities. For example, there are affinity crews for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community, LGBTQ+ youth and young adults, BIPOC, bi-lingual individuals, military veterans, women, and other populations.

The effects of climate change are increasingly apparent. Temperatures are rising, precipitation patterns are shifting, and more extreme events – like stronger storms, larger wildfires, major floods, and record heat – are becoming more common.

For many years, there have been calls to expand the modern Corps movement to engage more young people in climate resilience work and addressing backlogged projects on public lands. These calls increased during the COVID-19 pandemic; many see a revived CCC as a way to put people to work on critical conservation projects, provide job training to America’s youth, and help protect parks during a time of increased outdoor recreation.

Since 2020, more than a dozen bills have been introduced in Congress to create a Civilian Climate Corps. In addition, on January 27, 2021, President Biden signed an executive order that called to create a Civilian Climate Corps to “mobilize the next generation of conservation and resilience workers and maximize the creation of accessible training opportunities and good jobs.” The President has also included funding for a CCC in his budget proposals.

At The Corps Network, we believe the infrastructure and experience of the existing community of nearly 150 Corps programs can be a strong foundation for a national Civilian Climate Corps (CCC).

We also believe that funding to launch a CCC already exists. The House-passed Build Back Better Act included $20 billion ($15 billion for AmeriCorps and $5 billion for the Department of Labor) for CCC participants and $10 billion (for federal land and water management agencies) for CCC projects. Because the Senate could not pass a budget reconciliation package with any funding for social services, the $20 billion for CCC participants was stripped from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), but the $10 billion for CCC projects was included. In fact, between the IRA and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), there is as much as $27 billion for climate resilience, conservation, and green infrastructure projects. A fraction of this funding could be designated to establish and support a Civilian Climate Corps.

The Corps Network supports investment in a modern CCC that centers equity and environmental justice. A national program must:

Ninety years ago, the Civilian Conservation Corps transformed our landscape, helped lift thousands of families out of hunger and poverty, and provided 3 million young men with job training, discipline, and a sense of purpose. Today, our country has an opportunity to reimagine the CCC model. A national Civilian Climate Corps can help build our climate resilience, train the conservation workers we need, and address environmental injustice.

As the Chief Operating Officer, Marie has managed the day-to-day operations of The Corps Network for more than a decade. Marie supervises The Corps Network’s contracts as well as the organization’s private and federal partnerships with AmeriCorps, the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and other national organizations and agencies.

Marie was instrumental in the creation of GulfCorps, a conservation and workforce development initiative focused on training local young adults for careers in the growing restoration economy along the Gulf of Mexico. GulfCorps is now a multi-million-dollar program that has engaged hundreds of young people in job training and hundreds of thousands of hours of critical conservation work. Marie has also overseen The Corps Network’s impactful work with the U.S. Forest Service on such initiatives as the Resource Assistants Program – a rigorous internship initiative targeted at engaging underrepresented populations in natural resources work – and the Urban and Community Forest Program, which is helping strengthen America’s urban tree canopy and diversify our forestry workforce. Additionally, Marie oversees The Corps Network’s Corps Project Assistance program, which has been working with the National Park Service to scope Corps-appropriate projects at parks throughout the country, helping inspire a new generation of public lands professionals.

Marie has a wealth of experience in non-profit operations and management. Prior to joining The Corps Network in 2014, Marie spent 15 years as the Director of Programs and Development for the Citizens Conservation Corps of West Virginia (CCCWV). Marie was involved in the development and implementation of several innovative programs, including the first Brownfields Job Training Program in West Virginia. Marie has served on the board of directors for several organizations, including NASCC (National Association of Service and Conservation Corps – now The Corps Network); WV Development HUB; Harpers Ferry Job Center Community Council; American Cancer Society; and Main Street Martinsburg. She currently serves as a board member of American Trails, where she is co-chair of the development committee.

Marie holds bachelor’s degrees in political science and sociology, as well as a master’s degree in public administration. She studied at Concord University, Old Dominion University, and West Virginia University. Go Mountain Lions, Monarchs, and Mountaineers! In her spare time, Marie enjoys playing nine holes of golf, listening to great jazz music, and watching college football.

As the Government Relations Manager, Meghan assists The Corps Network’s Government Relations Team with Corps advocacy through administration and Congressional outreach as well as environmental and workforce development policy research.

Meghan is a graduate of the George Washington University with a bachelor’s degree in political science and communication. During her undergraduate career, Meghan interned in both the House of Representatives and the Senate where she discovered a passion for environmental advocacy and sustainability. Meghan was also a member of Alpha Phi Omega, a gender inclusive community service-based fraternity focused on volunteering at various service sites throughout the DC community.

Outside of work, Meghan enjoys running, finding new vegetarian dishes, and keeping up with reality TV.

(she, her, hers)

Thomas joined The Corps Network in 2020 as a Program Associate. His responsibilities focus on helping The Corps Network recruit and manage interns for the U.S. Forest Service Resource Assistants Program (RAP). He works in additional capacities by communicating effectively with the USDA Forest Service, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the National Park Service. As a Program Assistant, Thomas is responsible for maintaining communications between RAP interns about their specific experiences and projects.

Thomas originates from New Orleans, LA but attended college in Washington, DC, receiving his Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from The Catholic University in 2019. He has held several internships around DC, but he has always been passionate about serving his community and looks forward to the exciting opportunities offered by The Corps Network to assist communities and people who are in need.

Pronouns: He/Him/His

Shytia “Tia” Blakney was born and raised on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi. She has an Associate’s Degree in Business and is close to completing her Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration. She enjoys shopping and spending time with her beautiful children ages 10, 6, and 4. Tia worked at CLIMB CDC for 3 years managing their Workforce Innovation Opportunity Act program. She was responsible for managing their employer partnership portfolio and placing young people in externship opportunities. Her passion is working with opportunity youth to help them become employable and self-reliant. During her time at CLIMB, she worked very closely with young people creating their Individual Development Plans and assisting them with meeting their education and employment goals. She worked with the conservation and environmental programs, as well as, the general workforce development operation. Prior to CLIMB, she worked at the Harrison County Adult Detention Center as a Correctional Officer.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

As Communications Manager, Asia assists in creating written, graphic, and video content. Originally from Long Beach, CA, she received her Bachelor’s degree in English Writing with a minor in Mass Communications from Loyola University New Orleans. Post-graduation, she moved to Portland, OR, where she was the Community Manager for a small business, running their social media and events. Now located in Washington, DC, her passion is storytelling through digital content. She has worked with and managed various brands such as publishing companies, luxury magazines, tourism boards, and nonprofits. In her most recent position, she worked with the Communications team at Latino Corporate Directors Association to increase gender, racial, and ethnic diversity on corporate boards. She aspires to continue a career in Communications specifically working with organizations based in nonprofit, policy/advocacy, and social justice work. She enjoys traveling, concerts, and spending time with her two dogs, Cronus and Wilson.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Communications Coordinator

Edward joined The Corps Network in 2022 and supports the communications team by managing various digital campaigns highlighting Corps. Edward previously served as a Corpsmember with the Bureau of Land Management as an environmental educator and wildlife researcher on the Oregon Coast. Following his Corps service, Edward worked for Environment for the Americas in Boulder, Colorado to continue to follow his passion for wildlife conservation and environmental education. In this role, Edward partnered with the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service to promote federal internship programs.

Edward lives in Washington, DC and is a student at Georgetown University’s M.S. in Environment and Sustainability Management program. In his free time, Edward enjoys playing roller and ice hockey, reading nonfiction, and cooking.

Maame Aba Ackon joined The Corps Network as the Executive Assistant in 2022, where she works with the executive office.

Maame received her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology and Sociology from Frostburg State University and worked with a non-profit organization in Baltimore prior to joining TCN.

Outside of work, Maame loves to watch Jeopardy, binge watch Bob’s Burgers, and get buried in a good book.

Grants Coordinator

Tatiana Cleveland joins The Corps Network as a Grants Coordinator. She assists the grant team in processing reimbursement requests from our many Corps and helps to ensure responsible and fiscally sound grant stewardship. As a self-proclaimed nomad, her career in national service has taken her to places such as Austin, TX, Atlanta, GA, and now she is so glad to be in Washington, DC. Tatiana attended UNC Pembroke, where she obtained her B.S. in Mass Communications with a focus in Public Relations. She holds a MA from the UNC Wilmington in Liberal Studies, and is currently working on a second Master’s in Nonprofit Administration from Louisiana State University Shreveport. Tatiana is a 3x AmeriCorps Alumna having served in NCCC, VISTA, and State and National. Previously Tatiana has managed several AmeriCorps VISTA projects over her career, which started with the United Way in Wilson County North Carolina after her last service term. In her most recent role, she served as a Portfolio Manager with the South Central Regional Office of AmeriCorps. In her free time, she enjoys yoga, learning about sociology, and volunteering with her sorors of Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. Tatiana is lucky to be a mom of to a lovely daughter, Camille, age 10, and a very happy baby boy, Emory, who is 8 months.

Program Manager

Vivian Meade joined The Corps Network in 2024 as a Program Manager. Vivian graduated from Northern Illinois University (NIU) in DeKalb, IL, with a bachelor’s in Spanish and Latino and Latin American Studies in 2020. During her time at NIU, Vivian conducted research and contributed over eight oral history recordings and transcriptions to the Latinx Oral History Project. Shortly after graduating, Vivian joined AmeriCorps VISTA where she served at the Black American West Museum & Heritage Center. In this role she was able to use her passion for history to educate and uplift the Black community of Denver, CO.

Vivian has experience working alongside the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service to provide youth internship opportunities for Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. Prior to joining The Corps Network, Vivian managed The Latino Heritage Internship Program, a service corps, and an individual placement program. She is passionate about fostering safe spaces for BIPOC communities in our public lands and providing opportunities for youth to grow professionally in cultural and natural resource management. Vivian’s interest in agriculture came from her multi-generational family’s farm in Illinois, and she is eager to uplift the next generation of climate stewards while managing the Working Lands Climate Corps.

In her free time Vivian loves to travel, explore museums, go hiking and bird watching. She is an activist, an educator, a musician, and currently resides in Colorado with her pup and two cats.

Data Coordinator

Katie began her journey at The Corps Network as an intern in late 2023, working in partnership with Agents of Discovery. She transitioned into a full-time position as a Data Coordinator under the Member Service Team in 2024.

Adopted from China, Katie grew up in Portland, Oregon, and has since lived in various states across the country and currently resides in Baltimore, Maryland. She earned a Bachelor’s degree in Animal Science from The Ohio State University. Before joining The Corps Network, Katie completed a service term with the Maryland Conservation Corps.

In her free time, Katie enjoys playing in a community orchestra, training for open water races, and spending lazy days with her dog Dvorák, and two cats, Asimov and Dostoevsky.

Jim Lyons began his career with the US Fish and Wildlife Service then served as Policy Director for the Society of American Foresters before joining the House Committee on Agriculture where he led development of the conservation and forestry titles of the 1990 Farm Bill. President Clinton chose Jim to serve as USDA Under Secretary for Natural Resources and Environment where he oversaw the Forest Service and the new Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). He was an architect of President Clinton’s Northwest forest plan, helped protect national forest roadless areas, and also led efforts to promote greening of disadvantaged communities in major cities across the nation by advancing the Forest Service’s Urban and Community Forestry Program and launching “URP” – the Urban Resources Partnership. Jim was Interior Department Deputy Assistant Secretary for Lands and Minerals Management in the Obama administration where he helped lead efforts to conserve the Greater sage grouse, advance wind and solar energy on public lands, and advance strategies to combat rangeland fires across the West. Jim has been a Lecturer and Research Scholar at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies (now School of the Environment) and recognized as a distinguished alum by Yale. He now serves as a consultant on natural resource policy, conservation, and climate issues.

Natural Resource Management Expert

Leslie Weldon is an experienced leader in natural resource management and organizational development. Over the past 41 years, Leslie served in a diversity of senior executive and field-based positions within the USDA Forest Service. From 2018-2022 Leslie was Chief Executive for Work Environment and Performance. In this role, she championed system change to ensure workforce diversity, equity in program delivery, and leadership development.

From 2012 through 2018 Leslie served as Deputy Chief for National Forest System where she guided national natural resource policy, oversight and strategic direction for managing watersheds in the 193 million acres of National Forests and Grasslands. From 2009 – 2011, Leslie served as Regional Forester for the Northern Region of the Forest Service providing oversight and supporting collaborative landscape forest restoration and large landscape conservation efforts on 28 million acres of National Forests and Grasslands as well as State and Private Forestry programs in Northern Idaho, Montana, and North Dakota. Most recently Leslie was appointed by Secretary Tom Vilsack to serve as the inaugural Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer for the United States Department of Agriculture, where she served as the champion for USDA’s ongoing efforts to support a workforce that represents the citizens we serve, who have a sense of value and belonging, and who can thrive in their public service mission. She retired from federal service in March 2023.

Leslie, who began her career with USFS as a teen when she worked two summers on the Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia in the Youth Conservation Corps, has been a consistent and vocal champion of youth conservation and service corps programs, resulting in the highest ever Forest Service youth enrollment and public private funding partnerships from 2013 through 2017. Leslie currently serves on the boards of Arbor Day Foundation, Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative, University of Washington Center for Environmental Forensic Science, and Trout Unlimited. She earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in Biological Sciences from Virginia Tech. Leslie is married to Mike Weldon. They have twin adult sons, both of whom are pursuing careers in natural resources.

Laura Herrin joined ACE in 2018 as President and CEO. In the time since joining, ACE has grown in size and stature and is recognized as one of the nation’s premiere conservation corps. Laura has introduced three pillars to ACE as the organization strives to be the Program, Partner, and Workplace of Choice. Celebrating its 20th year, ACE has developed signature programs and worked on a variety of projects in all 50 states and several US Territories. Laura has a long tenure in the conservation corps arena. Prior to her role at ACE, she spent fifteen years with the Student Conservation Association, ultimately as its Senior Vice President for Programs. During her time at SCA Laura wore many hats including program and partnership development and implementation, risk management and safety, innovation, and organizational growth. Additionally, Laura has a long connection with The Corps Network. As a prior member of the Board, Laura was part of the process to update TCN’s organizational mission and was a member of the CEO hiring team. Laura is currently serving on the Corps Council for a second time and is rejoining the Board of Directors as a representative to the Board from the Corps Council. Additionally, in 2017-18 Laura worked directly with The Corps Network supporting fund development and partnerships. Laura holds a bachelor’s degree from Wheaton College (MA) and a Master’s Degree in Organizational Management and Leadership. She is a certified black belt in Innovation Engineering.

Louis Caldera has been a life-long champion of creating opportunities for young people to get a good education and too serve others. He joined the Clinton Administration as COO of the Corporation for National Service before being asked to serve as the 17th Secretary of the Army where he led the nation’s largest employer of young people. He later became president of the University of New Mexico. The son of Mexican immigrants, Louis started his career as an Army officer, lawyer and California legislator. Today, he teaches law at American University in Washington D.C., and he is a founder of the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration, an alliance of college and university presidents that advocate on behalf of Dreamers and international students. Louis is a graduate of West Point, Harvard Law School and Harvard Business Schools.

Michele Bolos is the Chief Executive Officer and Chair of the Board of Directors of Next Tier Concepts (NT Concepts), a national security solution provider for the US Government. In this role, Ms. Bolos oversees strategic direction, organic growth plans, and a culture of respect in the company. When founding NT Concepts in 1998, her guiding principle was to innovate and deliver high value mission critical solutions without compromising on exceptional customer service. This principle is the foundation of our success.

Prior to starting NT Concepts, Ms. Bolos worked for Alfa-Laval Thermal, Mobil Oil, Talus Corporation, and API/WANG Global where she led complex software engineering efforts for the commercial and federal marketplace. As CEO of NT Concepts, Ms. Bolos was named the 2016 Executive of the Year for companies $75 million to $300 million as part of the Greater Washington GovCon Awards.

Ms. Bolos is committed to fostering a service-inspired community by empowering employees to pursue their passion in service initiatives. She believes that a company grows stronger when employees work together to serve causes they care about. The company’s platform, #NTC_GivesBack, donates countless hours and resources, both domestically and internationally, to a variety of 501(c) organizations.

Ms. Bolos earned a Bachelor of Science in Information Systems from Virginia Commonwealth University. She maintains an active role in the professional services industry by serving on the Board of Directors and Executive Committee of the Professional Services Council (PSC) and on the Board of Directors of the NOVA Chamber of Commerce. She is actively engaged in community philanthropy by serving as the Chair of the Board of Directors for Leadership Mission International, the Board of Directors of Gabriel Homes and The Corps Network.

bchambers@corpsnetwork.org

Bailey Chambers joined the Corps Network in early 2024 as an Administrative Assistant. Originally from Massachusetts, she received her degree in Environmental Science and Policy from Clark University with a focus on the intersections of environmental and agricultural policy. After graduating, she moved down south to Tennessee, where she spent two years farming organic vegetables and managing the production of gourmet mushrooms. She found her way to The Corps Network after moving to Washington, D.C., to pursue a career in mission-focused non-profits.

Outside of work, Bailey loves gardening, reading, and spending time with her husband Jack, and two dogs, Goose and Moe.

Pronouns: She/Her/Hers

DERRICK CRANDALL — is Counselor to the National Park Hospitality Association and CEO of Outdoor Solutions USA. He recently retired from the American Recreation Coalition/Outdoor Recreation Roundtable after 37 years as its President. He Co-Chairs the Coalition for Recreational Trails and was Vice Chair of Interior’s Outdoor Recreation Advisory Committee. He received Presidential appointments to the President’s Commission on Americans Outdoors from 1985 to 1987 and the President’s Commission on Environmental Quality in 1991. He served on Brand USA and Western Governors Association advisory panels and was Chairman of the Take Pride in America Advisory Board, appointed by the Secretary of the Interior. He was a Founding Director of the National Forest Foundation, appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture. Among the dozens of public-policy efforts in which he has played a central role are Great Outdoor Month, the National Scenic Byways Program, Recreation Fee Demonstration Program, Recreational Trails Program, Wallop-Breaux Program, unification of federal campground reservations and the National Recreation Lakes Study Commission. He has received numerous national awards, including Chevron’s Conservation Award, induction into the RV Hall of Fame, a Centennial Award from the Forest Service, and Interior’s Spirit of Take Pride Award. USA Today references him as “the outdoor guru.” Mr. Crandall attained Certified Association Executive and Fellow designations from the American Society of Association Executives (ASAE) and served on its board for seven years, including two terms as Vice Chairman. He now enjoys connecting his five grandkids, ages 7 to 13, with the Great Outdoors.

jchesney@corpsnetwork.org

Jennifer has approximately 20 years of experience serving within her local communities. She earned her Bachelor of Arts in Education from the University of Mississippi in 2003 and her Master of Science in Counseling and Psychology from The University of West Alabama in 2012. During her career as an educator, Jennifer served as a licensed classroom teacher and tutor, elementary science teacher, Anatomy and Physiology instructor, Earth Science instructor, and Environmental Science instructor. As a Certified Mental Health Therapist, Jennifer practiced as a school-based child and adolescent therapist, day treatment therapist, outpatient child and family therapist, and in-home therapist. She has also worked in school attendance enforcement for the MS Department of Education, has experience working in social services and case management, and previously served as a Public Relations Director, Employee Assistance Program Coordinator, and Behavior Specialist. Jennifer joined The Corps Network as a Program Coordinator for GulfCorps and Delaware River Climate Corps in 2023. In her leisure time, Jennifer enjoys spending time with her family and traveling.

slizana@corpsnetwork.org

Sherrell Lizana is a graduate of the University of Southern Mississippi and native of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Being from the coast and an earth sign (BIG Capricorn energy), she has always loved nature and enjoyed outdoor activities to include gardening, fishing, and outdoor farmer’s markets. She embarked on her service journey after witnessing and experiencing the devastation that Hurricane Katrina left on her community in 2005.

This commitment to service led to various nonprofit management and human capital development roles alongside Boys & Girls Clubs, International Relief & Development and statewide planning and development districts, to bring about change utilizing our greatest resource, our workforce. She is passionate about economic and workforce development and teaches others that your income is a tool to build self-sustainability for yourself and future generations. Sherrell also enjoys karaoke, roller skating, listening to podcasts, and creating charcuterie boards.

As a Communications Coordinator, Emma assists The Corps Network Communications Team with content creation and strategy and collaborates with external partners to advance The Corps Network’s mission.

Emma is a graduate of James Madison University with a bachelor’s degree in History and Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication. While in college, Emma served as a tutor at her university writing center and interned for her New York district senator where she discovered a passion for working within the public sphere. She has also had the opportunity to intern in London for the London Business Matters magazine.

Outside of work, Emma enjoys exploring new places, hiking with friends, and tasting the newest local cuisine.

Allen Dietz has over 35 years of experience working with non-profit organizations. He has managed or provided technical support to AmeriCorps, VISTA, and Senior Corps programs for the past three decades. Allen founded and managed a large statewide AmeriCorps program in Texas, served as the Chief Operations Officer for the Washington Service Corps, and was the director of a Retired Senior Volunteer Program.

Allen was deeply involved with the development of The Corps Center of Excellence Accreditation Standards for Service and Conservation Corps, and currently helps manage The Corps Network’s national accreditation process.

Allen lives on the edge of the North Cascades in Washington State and enjoys hiking, kayaking, and skiing in his free time.

Pronouns: he/him/his

Jackie joins the Corps Network as the Director of Workforce Development, where she will focus on expanding national workforce initiatives, partnerships, post-placement employment outcomes, Apprenticeships, and workforce project funding. With over two decades of expertise in organizational design, strategic planning, and program management, Jackie has a successful track record in leading government workforce programs and managing contracts and grants for organizations like the Department of Labor (DOL) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). She excels in building cross-functional teams, optimizing performance improvement measures, and leading organizational change initiatives. Her passion lies in connecting underserved marginalized populations with equitable access to career pathways, higher education, and addressing Social Determinants of Health.

In addition to her previous leadership roles, Jackie has extensive experience in strategic consultancy, contributing to federal projects with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), the Department of Labor (DOL), and the U.S. Department of Education (ED.) in which her responsibilities encompassed federal proposal development, apprenticeship implementation, guiding national program development initiatives, informing green jobs research, and federal project grant management.

Jacqueline holds a Master of Education in Adult Learning and Workforce Education, a Master of Science in Management, and a Bachelor of Arts in Marketing. She is a Certified Workforce Development Professional, Certified Process Improvement Manager, Certified Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the Workplace Manager, and Certified Change Management Professional. She also holds various other certifications in project management, Lean Six Sigma, and professional and organizational development.

In her free time, Jackie cherishes family time with her husband, Thoris, and their three children, Avery, Eva, and Kailyn. Together, they engage in various activities, including family movie/game nights, travel adventures, candle-making, and lively karaoke sessions featuring beloved 80s and 90s songs. Additionally, Jackie finds relaxation, rejuvenation, and her ZEN! through the practice of study, meditation, and Hot Yoga.

On September 30, 2019, David Vela, a 29-year career veteran of the National Park Service (NPS), was named Deputy Director, exercising the authority of the Director of the National Park Service. He had been serving as Deputy Director of Operations since April. Vela previously served as superintendent of Grand Teton National Park and the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway from March 2014 to April 2019. Prior to assuming his Grand Teton post, Vela served as associate director for Workforce, Relevancy and Inclusion in the NPS Washington headquarters where he administered a $32 million-dollar operational budget with 153 employees, and served as a key advisor to the NPS Director and Deputy Director on the full spectrum of strategic Human Capital Management issues, initiatives, and policies. His national program areas included: Human Resources, Learning and Development, Equal Opportunity, Youth, and the Office of Relevancy, Diversity & Inclusion. Vela began his NPS career in 1981 as a cooperative education student at San Antonio Missions National Historical Park in Texas, and later became a permanent park ranger. From 1987 to 1998, Vela worked in a variety of federal posts outside the NPS, and retired from the agency in September 2020. Vela is the recipient of numerous awards both within and outside of the National Park Service for leadership and performance excellence. He and his wife, Melissa, have two children, Christina and Anthony, and eight grandchildren.

Monique Miles is the Vice President of Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions and Director of Opportunity Youth Forum, Prior to joining the Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions, Monique was the Director, Postsecondary Achievement at the National Youth Employment Coalition (NYEC). In her role at NYEC, Monique oversaw the Postsecondary Success Initiative, a national pilot that supported Community Based Organizations (CBOs) across the country to design and implement postsecondary programming, in partnership with local institutions of higher learning, for students who were disconnected from education.

Monique began her career in education reform working as a Literacy Instructor at Youth Opportunity Boston. In this role Monique worked directly with students remanded to the Massachusetts Department of Youth Services (DYS) to design and deliver education and career development curriculum. Monique went on to serve the same population of students through political advocacy initiatives at the Commonwealth Corporation (CommCorp).

Monique earned a Bachelor of Science from Springfield College and a Master’s in Education, Policy & Management from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Monique serves as the Vice-Chair of the Board of Trustees at the Pomfret School. She also serves on the Advisory Board of Tulane University Cowen Institute of Public Education Initiatives. She is on the board of Independent Trust and The Corps Network.

scarter@corpsnetwork.org

Shellie Carter lives on the beautiful Gulf Coast of Mississippi and joined The Corps Network(TCN) as a Program Coordinator working with the GulfCorps program. She has recently joined the TCN accreditation team. Shellie has a communication and public relations education, but her passion and work experience has been human services. Shellie worked for local community development organizations including Corps programming for more than 15 years. She has worked in corps, program, and organizational development starting and managing human services programs that have invested more than $50 million dollars into the local community. She has specialized in workforce development for opportunity young adults and within marginalized communities. Some of these programs include Youth Build, WIOA, AmeriCorps, homeless services and re-entry programs. Her interests include Cruisin’ The Coast, Mardi Gras, event planning, decorating and in her spare time she loves to spend time with her grandchildren.

As a Communications Associate, Ed supports The Corps Network Communications Team by creating and managing media content promoting Corps. Ed received his bachelor’s degree in Political Science with a minor in Media Studies from DePauw University. During college, Ed volunteer coached for a special needs travel ice hockey team in Indianapolis (Go Twisters!) and served as a teaching assistant at DePauw University and Ewha Women’s University in Seoul, South Korea. Ed also spent a summer on Capitol Hill as a congressional intern and later completed a 6-month environmental education and outreach internship on the Oregon Coast with the Bureau of Land Management at Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area. Before joining The Corps Network, Ed worked as a Communications Lead for Environment for The Americas in Boulder, CO.

Ed lives in Colorado and enjoys playing ice/roller hockey, petting dogs/cats, and exploring natural spaces.

Pronouns: he/him/his

cplato@corpsnetwork.org

Carole M. Plato joined The Corps Network as Grant Manager on October 1st, 2023, where she works with the Director of Grants Management in managing the grant and awards programs.

After living and traveling around Europe while enlisted in the United States Army, she settled down in the Washington, DC area after retiring from active-duty service. Carole is an alumnus of University of Maryland Global Campus where she majored in Communications and brings a wide variety of administrative expertise from several industries. From biotech to government relations, patent filings for intellectual property, global communications to enterprise solutions for cloud storage. She is excited to be working alongside her colleagues to support the mission of The Corps Network and its members.

She is also an active member and Secretary in a local chapter Toastmasters International; enjoys walking and biking in her community of Hyattsville and continues to travel as often as possible.

Michael Summers was born on November 19, 1972, and is originally from North Carolina. Michael has been a resident of Maryland since 2001. He received his Bachelor of Arts degree from North Carolina A&T State University and Master of Liberal Arts from The Johns Hopkins University.

Mr. Summers has been a Business Development Manager that employs an entrepreneurial and collaborative approach to achieving results for business and community leaders, non-profit organizations, government agencies through creative and innovative solutions.

He is a former State Delegate to the Maryland General Assembly for Prince George’s County (Dist. 47). He is a former Member of: The Cheltenham Youth Facility (CYF) Advisory Board, Prince George’s Co. School Mental Health Initiative Advisory Board, Prince George’s County Workforce Investment Board’s Youth Council, and Prince George’s Co. Schools Interagency on Attendance Council. He is also a co-founder of Cheverly Village, a community organization that assists senior residents age in place.

Michael has been a recipient of; the Civic Engagement Award from the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Foundation of Prince George’s County, Outstanding Contributor Award for his involvement with the Prince George’s Co. Local Management Board, Prince George’s County Public Schools Community Partner Award, Maryland Municipal League Outstanding Friend of Municipal Government Award, and a Council of State Government (CSG) Henry Toll Fellow.

Leslie began with the Human Environment Center in 1984 and transitioned to The Corps Network when it was created in 1985. Since she began, Leslie has planned numerous conferences, designed and edited a quarterly newsletter, and directed member services. Leslie has taken on almost every responsibility possible at one time or another, and has become one of the most knowledgeable leaders in the Corps Movement, sought out for her wisdom, command of Corps history, and expertise in AmeriCorps programs and initiatives.

Leslie previously administered The Corps Network’s AmeriCorps Education Award Program (EAP). She created TCN’s AmeriCorps Program Manual as well as a document on how to get the most out of the AmeriCorps Education Award (scholarship), which includes non-traditional uses of the award. She also ensures compliance and provides technical assistance to TCN Subgrantees in our Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) AmeriCorps grants.

Throughout her tenure, Leslie has developed a cache of tools for national service and youth development programs and has emerged as one of the leaders of the EAP, serving on numerous working groups for CNCS. She also provides training to Subgrantees for the eGrants Portal on-line member management system, AmeriCorps Compliance and other aspects for running a successful, compliant program. In addition, she worked with Willis Towers Watson to develop The Corps Network’s Health Insurance Plan for Corpsmembers and AmeriCorps members.

Leslie has a degree in Textile Design and likes to spend her free time creating beautiful quilts and other fabric items. Attendees at the special AmeriCorps session at TCN’s Annual Conference always get a fun fabric craft or toy to take home.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Thank you for your interest. This library is reserved for employees at member organizations of The Corps Network. You must sign in to view content. This library is NOT intended for Corpsmembers or interns. Please log in below or click here to create a user account.

Interested in membership in The Corps Network? Please contact Bobby Tillett, btillett@corpsnetwork.org

Stephanie Mathes is a native Mississippian with over 20 years of nonprofit management and workforce development experience. She attended California State University, Long Beach studying Philosophy with an emphasis in Pre-Law. She, and her husband Bruce, have three college aged children. Her favorite pastimes are gardening, painting, and being involved with her local church.

Stephanie’s previous roles at The Corps Network included Director of Special Initiatives and Director of Gulf Operations. Prior to her tenure at The Corps Network, Stephanie was the co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of a local community development organization (CDC) specializing in human development programs including workforce training for opportunity and at-risk youth. Over the course of her 20-year career, Stephanie has worked with nonprofit organizational management, project development and the implementation of over 135 million dollars of federal funding. Besides the workforce training institute, her project implementation experience has included prevention of child abuse, micro-enterprise, social enterprise, juvenile justice programs, housing and homeless programs, and disaster response/recovery. While at the CDC, Stephanie developed and managed the organization’s conservation corps program as part of their Environmental and Conservation employability track. Stephanie is very involved in her community serving on a variety of local Boards of Directors and committees. She completed Leadership Gulf Coast, Class of 2014 and is a graduate of the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Business program.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Hannah joined The Corps Network in 2021 as the Member Data Coordinator. She graduated from the University of Illinois with a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Science and promptly moved west to work for various public land agencies. Much of her previous job experience has been seasonal field work focusing on surveying wildlife and implementing habitat restoration efforts in the southwest region of the country. Her Corps experiences range from leading a crew with Arizona Conservation Corps that removed invasive trees in the Verde River watershed, to supporting crews of her own as a Program Coordinator with Northwest Youth Corps.

Outside of work, you will most likely find her exploring the Pacific Northwest with her dog Ravioli going backpacking, hiking, and attempting to fly fish.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

As the Director of Communications, Hannah develops and produces written, graphic and video content. She also oversees The Corps Network’s website and social media accounts. Over the years, Hannah has created countless publications about Corps, written articles and opinion pieces for national outlets, and assisted in the planning efforts for The Corps Network’s events. She has developed resources for helping Corps improve their communications efforts, and leads a working group of communications and marketing professionals across the Corps community. Hannah was the lead author of the book Join the Crew: Inspirational Stories of Young Adults in America’s Service and Conservation Corps.

Hannah received her bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Mass Communications from George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs. While in college, Hannah volunteered at the National Air and Space Museum, and volunteered in DC Public Schools through DC Reads (a tutoring program) and Prime Movers (a journalism education program). She also spent a semester interning with the National Alliance to End Homelessness, and spent over a year interning and writing for Street Sense; a DC-based newspaper focused on raising awareness about homelessness.

Hannah enjoys warm jackets, houseplants and figs.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

As the Director of Member Services, Bobby coordinates and manages activities designed to identify and meet the needs of TCN members, including administration of membership information, management of efforts to retain and recruit members, assistance with the Corps Center of Excellence Accreditation program, and the coordination of member benefits. Member benefits include technical assistance offerings, trainings, resources, partner relationships, events and new initiatives as they arise.

Prior to working at The Corps Network, Bobby completed two AmeriCorps terms-of-service with the Montana Conservation Corps as both a crewmember and a crew leader. He served on a backcountry wilderness trails crew as well as a roving habitat restoration crew. Bobby also worked as the Government Relations Intern at The Corps Network where he assisted the Director of Government Relations as well as provided logistical support for the Public Lands Service Coalition.

Bobby graduated from the University of Mary Washington with a BA in International Affairs. Outside of work, he enjoys running, documentaries on Netflix, and watching the Wizards and Nationals.

Pronouns: he/him/his

Bridget Street joined The Corps Network in 2022 as the Youth Program Assistant. Bridget works in close partnership with the National Park Service, Interior Region 1 to coordinate planning, monitoring, and reporting outcomes of youth and young adult programs in national parks throughout the northeastern United States. Prior to her work with The Corps Network, Bridget served as a Community Volunteer Ambassador at Weir Farm National Historical Park through Conservation Legacy’s Stewards Individual Placement program. She has a passion for connecting communities and conservation and holds degrees in Earth Science and Linguistics from Columbia University. Outside of work, Bridget enjoys dancing, concerts, and outdoor adventures.

Jeremy “Jerry” M. Jacobs, Jr. is Chief Executive Officer of Delaware North and an alternate governor to the Boston Bruins of the National Hockey League (NHL). He shares the CEO and alternate governor titles with his brothers, Lou and Charlie Jacobs.

Delaware North is a family-owned global leader in hospitality, with operations in food and retail at airports and sports venues, hospitality services at parks and major tourist attractions, hotel ownership and management, gaming operations, fine dining and catering, and sports facility ownership and management. In 1995, Delaware North built a new multi-purpose arena in Boston, Mass., that is currently home of the Bruins and the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association (NBA). Over the past 25 years, the TD Garden has undergone many transformations and is now considered one of the most innovative and celebrated venues in North America.

Delaware North maintains a global headquarters in Buffalo, N.Y. where the Jacobses are celebrated as longtime supporters of the University at Buffalo, a flagship institution in the State University of New York system. The university named and dedicated the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in 2015, in recognition of the Jacobs family’s many decades of philanthropy. Most recently, the Jacobs family contributed $30 million for the construction of the new, state-of-the-art medical school building in downtown Buffalo. The Jacobses also founded the Jacobs Institute, a medical innovation center focused on accelerating device development in vascular medicine.

The Jacobs family and Delaware North are significant benefactors to multiple non-profit organizations in Western New York and throughout the United States and world. Jerry serves on the Scholarship Board for Say Yes Buffalo, an organization dedicated to increasing high school and postsecondary completion rates for students in the City of Buffalo. He is a past member of Georgetown University’s Board of Regents and volunteers as an alumnus interviewer.

Jerry has additionally dedicated more than two decades of volunteer service to the United Way of Buffalo and Erie County, including past chairmanships of the organization’s board of directors and annual fundraising campaign, and is a past chair of the Nichols School’s Board of Trustees, where he founded the Jacobs Scholars program for high-achieving students with financial need.

Jerry is active in multiple business and civic organizations. He completed a term on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Travel and Tourism Advisory Board in 2015, and in 2018 he was named to the U.S. Secretary of Interior’s “Made in America” Outdoor Recreation Advisory Committee. He is an active member of the U.S. Travel Association’s CEO Roundtable and the Partnership for New York City.

Jerry completed an M.B.A. from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania and a B.A. from Georgetown University. He met his wife, Alice Jacobs, when they were both students at the University of Pennsylvania, where she earned a J.D. Alice is the chair emerita of the Western New York Women’s Foundation, president of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Board of Directors, and a member of the board of directors for the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo.

Jerry and Alice reside in East Aurora, New York. They have two children, Melissa and Justin.

Karen Pittman is the Co-Founder of The Forum for Youth Investment, and served as its President & CEO until February 2021, then transitioned to a senior fellow role to dedicate more of her time and energy to thought leadership. Karen has made a career of starting organizations and initiatives that promote youth development – including the Forum for Youth Investment, which she co-founded with Merita Irby in 1998. Karen started her career at the Urban Institute, conducting studies on social services for children and families. She later moved to the Children’s Defense Fund, launching its adolescent pregnancy prevention initiatives and helping to create its adolescent policy agenda. In 1990 she became a vice president at the Academy for Educational Development. In 1995 Karen joined the Clinton administration as director of the President’s Crime Prevention Council, where she worked with 13 cabinet secretaries to create a coordinated prevention agenda. From there she moved to the executive team of the International Youth Foundation (IYF), charged with helping the organization strengthen its program content and develop an evaluation strategy. In 1998 she and Rick Little, head of the foundation, took a leave of absence to work with ret. Gen. Colin Powell to create America’s Promise. Upon her return, she and Irby launched the Forum, which later became an entity separate from IYF. Under their leadership, the Forum has established deep roots as a national nonprofit, nonpartisan “action tank” – combining thought leadership on youth development, youth policy, cross-system/cross-sector partnerships and developmental youth practice with on-the-ground training, technical assistance and supports – fully committed to changing the odds that all children and youth are ready for college, work and life.

Jennifer Palmieri is a co-host of Showtime’s Emmy-nominated “The Circus.” She is the author of the Number 1 New York Times bestselling book Dear Madam President, and She Proclaims: Our Declaration of Independence from a Man’s World. Jennifer is one of the most accomplished political and communications strategist in the country. She served as White House Communications Director under President Barack Obama and was head of communications for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. Prior to joining the Obama White House, Jennifer was President of the Center for American Progress Action Fund, the advocacy arm for a premier progressive think tank. She was also national press secretary for the Democratic Party, White House deputy press secretary for President Bill Clinton, and national press secretary for the 2004 John Edwards for President campaign. She started her career as a legislative assistant for then Congressman Leon E. Panetta of California. Jennifer is a graduate of American University and lives with her husband Jim Lyons in Maryland.

Kionne McGhee grew up in South Dade public housing and went on to earn a bachelor’s degree from Howard University and a Juris Doctorate from the Thurgood Marshall School of Law. He was first elected to the Florida House of Representatives in 2012 for Florida House District 117 and served as the Minority Leader from 2018 to 2020, when he was elected as Miami-Dade County Commissioner for District 9. Commissioner McGhee is an accomplished attorney and the author of the bestselling-book “Conquering Hope: The Life You Were Destined to Live.”

His numerous affiliations include the Florida Trial Lawyers Association, Wilkie D. Ferguson Bar Association, and the Greater Miami Service Corps, where he serves as a board member. He is also President and founder of 2NOIT Media & Publishing, founder of Y.A.L.E. (Young Advocates Leading by Example), and president of Transitions, Inc. He has been named as one of Miami’s Rising Voices by AT&T and the Miami Herald and earned the Florida Self-Sufficiency Award in 2010. Commissioner McGhee is married to Stacy McGhee and is the father of Kionne II, Hayley and Hays.

Emily is from Mississippi and went to College at the University of Southern Mississippi to receive degrees in Psychology and Environmental Biology. She has worked in many roles, from Business Analyst to Alaska Crab Boat Biologist, but fell in love with the Conservation Corps world when she served as a Crew Leader for Wyoming Conservation Corps. Later, Emily joined the staff team at American Youthworks as a Field Coordinator for TxCC and then transitioned over to manage LACC. When she moved back to Mississippi this year, Emily was excited to see that the Gulf Operations team with TCN was hiring.

LaShauntya joined The Corps Network in 2016 as a Fellow to the Education and Workforce Development department and is now the Member Services Assistant. She brings 16 years of environmental service to her position. She started as an AmeriCorps member at Earth Conservation Corps, a DC-based environmental organization. She completed two terms and was asked to join the staff as a site manager. After six months, she was promoted to Youth Program Coordinator. She has been featured on 60 Minutes, NOW with Bill Moyers, and in People magazine. In her free time, LaShauntya enjoys spending time with her family, reading and traveling.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Tim was hired by TCN in July of 2022 as the Maintenance Action Team (MAT) Program Manager. The MAT assists the National Park Service (NPS) by developing project scopes of work and related cost estimates for small and medium sized parks. Funded through the NPS Legacy Restoration Fund (LRF), these projects will be staffed and executed by Service and Conservation Corps members.

Tim grew up in Yosemite National Park where he started his career with the NPS. His 40-year tenure with the Service included maintenance positions at Grand Canyon National Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and Mount Rushmore National Memorial. In his final position, Tim served as the Chief of Park Facility Management in the Washington Office, where he provided leadership and policy direction to ensure the effective stewardship of the Service’s constructed asset portfolio. Within this capacity, he also championed the transformation of NPS’s reactive style of maintenance to one that is proactive and rooted in industry best practices. Tim received an Associate of Arts degree in Liberal Arts from Fresno City College.

Ms. Dorsett is Executive Director of Greater Miami Service Corps where she directs fundraising and development efforts to sustain the organization; initiates public relations efforts to engender support from the public and private sectors of the community; and ensures the delivery of program services are effectuated with optimal results while meeting the changing dynamics of a global non-profit environment. Her primary areas of concentration include grant development and implementation; contract management and monitoring; personnel management; budget development; design and implementation of education, job training activities and coordination of social services.

During her over 30 years in public administration, Ms. Dorsett has served in numerous leadership positions including, former Chairperson of The Corps Network Board Directors (now Corps Council). She also served as Vice President and Treasurer of Unity of Miami Gardens Church; President and Vice President, Fountain Park Village Homes Association, and Health Committee Co-Chair, for Gamma Zeta Omega Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated. Ms. Dorsett currently serves as Assistant Treasurer of the Women’s Involved in Service to Humanity (WISH) Foundation, Vice Chairman of NieCat Foundation of Excellence, Incorporated, Vice President of the Florida YouthBuild Coalition, and Chairman of the Risk Management Committee of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated Gamma Zeta Omega Chapter and member of The Corps Council and The Corps Network Board of the Directors. In 2019, she was awarded by Legacy Magazine as one of the 50 top influential black business leaders and public official of the year. Ms. Dorsett received a Bachelor of Science Degree in Business Management from Florida Memorial University, and she earned a Master of Business Administration from St. Thomas University.

Austin Bowley grew up in Jackson, Mississippi and graduated from Davidson College in North Carolina in 2018. In his first year after college, he served an AmeriCorps term in Tallahassee, FL providing free vision screenings for preschoolers and free tax preparation for working class families and individuals. After completing his first AmeriCorps term, he moved to Pensacola, FL to serve another AmeriCorps term with the Conservation Corps of the Forgotten and Emerald Coasts (CCFEC).

Finding a home within conservation, Austin moved into a staff role with CCFEC for 2 years where he worked closely with the GulfCorps program. He particularly enjoyed working with young adults, helping them reach their personal and career goals. After years of missing his hometown, he moved back to Jackson, MS. Luckily, his friends at The Corps Network were hiring for the Gulf Operations team, and he joined The Corps Network in the summer of 2022, where he is able to continue working with young people.

In his free time, Austin enjoys making music as a guitarist and vocalist, playing soccer, and playing board games and video games with friends and family. His cats ensure he rarely has a moment to himself.

Tiffany Madison is an Alabama State University graduate that hails from Century, FL. Tiffany has an undeniable love for nature that has allowed her to engage in urban agriculture, sustainability, historic preservation, animal husbandry, community gardening, environmental education, and workforce development.

With a desire to lead future generations, Tiffany has worked in conservation and public land management for the last decade. Alongside agencies like the National Park Service, USDA Forest Service, and the State Botanical Garden of Georgia, she has cemented this path with her commitment and dedication for community growth and advancement.

Jordan Reeder joined The Corps Network as the Grants Coordinator in 2022, where she works with the Director of Programs to provide support across the diverse portfolio of Corps programs.

Jordan received her Bachelor’s degree in Health Care Management from Towson University and has worked with various non-profit organizations in the Washington Metropolitan area prior to joining TCN.

Outside of work, Jordan enjoys cycling, a good movie, and volunteering within her community.

Rachael Zwerin is responsible for assisting the Member Services Team in identifying and supporting the needs of The Corps Network’s member organization. Rachael was born and raised in Westchester, NY. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Sustainability from The State University of New York College at Oneonta. Rachael has prior experience volunteering with the non-profit organization Common Ground Relief in New Orleans, LA, working on coastal restoration projects to rebuild communities and wetlands along the coast of Louisiana. She also worked for two consecutive summer seasons as a Youth Program Assistant for Groundwork Hudson Valley as a crew leader for youth working on local conservation projects, such as trail restoration and invasive species removal. In her free time, Rachael enjoys traveling, kayaking, camping, and sunset picnics with friends.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Aileen Yelle is a native Mississippian with an MBA and over 20 years of small business, HR and project management experience. She has three grown boys, loves to cook, and loves to watch movies, football and sunsets on the water. She has traveled to almost every area of the country (and lived in a few different areas), but she chose to make her home on the southern shores.

Aileen has experience running a small construction business, working in human resources, and project management. She has worked in a variety of industries including computer software, wireless communications, manufacturing, beverage distribution, multimedia, finance and non-profit.

Prior to taking her current position at The Corps Network, Aileen worked with Climb CDC for five years, investing in Mississippi Gulf Coast communities through housing programs and workforce development for opportunity youth. During her last year with Climb, the organization had two Conservation Corps crews; Aileen was closely involved with hiring the crews and implementing the program.

“Working in the non-profit workforce development arena has been infinitely more satisfying than any job in a for-profit company because it allows me to merge my moral and spiritual principles with my daily work endeavors. I feel privileged to continue my career on a regional scale with The Corps Network, increasing the environmental, social and cultural impact I can have on my southern home.”

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Capri serves as the Director of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion at The Corps Network. Her focus has been on increasing exposure as well as opportunities in the environmental and conservation field for young adults of color. She has looked to deepen The Corps Network and the Corps understanding around institutional and structural racism and how it plays out in the work that we do. She is a graduate of New York University for both her BFA and MA. She has over 35 years of experience in education in NYC, Seattle, and now DC. She taught Media Studies at Seattle Central College as well as the Intercultural Communication course for international students where she was introduced to the concept of “Integrative Learning Communities,” which is a collaborative interdisciplinary approach to higher education. She was a Faculty member at the BA Completion Program at Antioch University Seattle where she taught the cultural studies courses, and then Director of Student Life and Disability Services at Antioch University Seattle.

Prior to joining The Corps Network, she was in NYC at Federation Employment Guidance Services (FEGS) in their Education and Youth Division where she developed the education program for their now signature Bronx program (serving over 400 young people a year) that works primarily with foster care youth.

She with her husband are the founders of “Rebuilding Haiti One Trip at a Time,” where they focus on changing the narrative of the country by engaging small groups in cultural and historical tours of the country.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Christian joined The Corps Network in 2021 as a Program Coordinator. Originally from Round Rock,TX, he received his bachelor’s degree in Environmental Policy with a minor in Math Informatics fromWesley College in 2020.Post-graduation, he moved to Biloxi, MS, where he started as a crew member atClimb CDC, eventually becoming a crew leader.Outside of work, Christian likes to spend time with his wife and two dogs.

Pronouns: he/ him/ his

Victor O. Robertson Jr. joined The Corps Network as the Director of Workforce Development in October 2021. In this role, he develops viable career pathways for Corpsmembers by working with Corps to strengthen their employer partnerships; expanding their training and credentialing offerings; and, building their supportive services to assist Corpsmembers who face barriers to employment and education.

Prior to joining The Corps Network, Victor spent eight (8) years at the Department of Employment Services (DOES) developing and implementing workforce programs for adults, youth, and special populations. During his time with DOES, he was responsible for was creating workforce programs and career pathways for individuals with barriers to employment including opportunity youth with a criminal record and lacking literacy and numeracy skills. In addition to developing and implementing workforce programs, Victor has a proven track record of establishing public-private partnerships; policy advisement; performance and compliance management, labor market analysis; and, providing technical assistance.

A proud Howard University graduate, Victor holds bachelor’s degrees in Psychology and African American Studies, as well as a Master’s of Social Work (MSW) with concentrations in Mental Health and Family and Child Welfare.

(he/him)

Danielle Owen has joined The Corps Network as the Director of Government Relations. In this role she works to develop and implement policy and legislative initiatives with a focus on conservation/natural resources, national service and youth/workforce development. She works closely with Congress and federal agencies on these issues.

Prior to joining The Corps Network, Danielle worked for 14 years in the office of former Congressman Melvin L. Watt, seven of those years serving as his Chief of Staff. Following her time in the House, she served as a Director of Governmental Affairs and then as a Deputy Assistant Secretary for Governmental Affairs in the Office of Secretary Foxx at the United States Department of Transportation. When not working, Danielle can be found in a bookstore searching for her next favorite book or talking about her adorable nephew, Owen, and her adorable niece, Emerson.

Pronoun: she/her/hers

chollingsworth@corpsnetwork.org

Candace Hollingsworth joined The Corps Network in January 2019 as the Director of AmeriCorps Programs. She now serves as Director of Programs.

Candace has a passion for service and improving the effectiveness of public sector organizations to advance their missions. She has 15 years’ experience in the nonprofit sector having assumed roles ranging from grants manager to virtual CFO and has managed projects of all sizes. However, Candace is no stranger to corps or The Corps Network. She cut her teeth in workforce development through service and conservation corps as the grants finance manager for the Conservation Corps of Greater New Orleans, a project of The Corps Network from 2008-2009. Since that time, Candace has kept positive youth development as a centerpiece of her work as the mayor of the City of Hyattsville. In that role she regularly works to build strategic partnerships and programming to create meaningful connections with young people to promote civic engagement, expand education and economic opportunity, and support the long-term sustainability of the city.

Candace is a graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy and received a Bachelor of Arts in African-American Studies from Emory University and a Master of Public Policy (MPP) specializing in education, family, and social policy from Georgetown University. When she’s not at work or banging the gavel, you can find Candace somewhere enjoying great coffee or bourbon and making friends laugh with animated stories and eerily accurate impersonations.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Dan has over 8 years of experience on staff with TCN member organizations (PowerCorpsPHL & The Work Group). As a Program Manager, Dan is currently focused on coordinating the multitude of communities and partnerships across four states, involved in the newly launched Delaware River Climate Corps (DRCC).

Dan graduated from the Pennsylvania State University with a BA in Environmental Studies. Upon graduating, Dan completed 1+ term-of-service as an AmeriCorps VISTA serving Greater Philadelphia.

Outside of work, Dan volunteers his time to improve Philadelphia’s environment as a Master Watershed Steward through the Penn State Extension office and a Philly Forest Steward with Philadelphia Parks & Recreation. He also enjoys visiting national parks, board games with friends, and science-fiction series.

Pronouns: he/him/his

Mary Ellen Sprenkel has been a long-time champion for youth. Mary Ellen came to The Corps Network in March of 2008 as Director of Government Relations. She was promoted to Vice President of External Affairs in 2011 and then appointed Interim CEO in May of 2012, prior to being selected as the CEO in October of 2012. During her tenure, Service and Conservation Corps have become better known programs to lawmakers and policymakers throughout the federal government. Legislation that would expand and bolster youth programs including Service and Conservation Corps has been routinely introduced in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. Under Mary Ellen’s leadership, in 2010 more than $63 million of American Recovery and Reinvestment Act projects were granted to Service and Conservation Corps throughout the country by 15 federal agencies. These projects provided youth with jobs and service opportunities while connecting them to public lands including national parks and forests. More recently, Mary Ellen has served as a member of the Federal Advisory Committee tasked with providing recommendations to federal land management agencies on how to implement a 21st Century Conservation Service Corps.

In addition to her productive time at The Corps Network, she has ten years of Capitol Hill experience, including two years on the House Committee on Education and Labor handling postsecondary education, training, and life-long learning programs. She also worked for Representatives Matthew G. Martinez (D-CA) and Nydia Velazquez (D-NY). Before joining The Corps Network, Mary Ellen was Vice President of Government Relations at the Education Finance Council, the national trade association for nonprofit and state based student loan providers. Prior to that, she spent two years as the Assistant to the President of the University of Montana.

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Paul Schmitz builds the collective leadership of organizations and communities to achieve greater social impact through his roles as Senior Advisor at The Collective Impact Forum and CEO of Leading Inside Out. He is an author, speaker, trainer, and consultant whose work focuses on leadership development, collaborative culture, racial equity, community engagement, and result-based strategies.

Paul is the author of Everyone Leads: Building Leadership from the Community Up (Jossey Bass, 2011). The book is based on lessons learned from 21 years leading Public Allies, an innovative leadership development program that helped more than 5,000 passionate and diverse young leaders across the country begin careers working for community and social change.

Paul is a faculty member of The Asset-Based Community Development Institute, and a board member of The Corps Network, Playworks, and The United Way of Greater Milwaukee. Paul previously served on the board of Independent Sector, the association of nonprofit and philanthropic leaders, and was the co-chair of Voices for National Service, which led advocacy for AmeriCorps and other national service programs. Paul co-chaired the 2008 Obama Presidential campaign’s Civic Engagement Policy Group, was a member of The Obama-Biden Transition Team and was appointed by President Obama to The White House Council for Community Solutions.

Paul is an honors graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. In 2014, Paul was appointed the first Innovator in Residence at Georgetown University’s Beeck Center for Social Innovation. He has also been recognized by The Rockefeller Foundation as a Next Generation Leadership Fellow, by the Nonprofit Times three separate years as one of the 50 most influential nonprofit leaders in America, and by Fast Company Magazine with their Social Capitalist Award for innovation. He lives in Milwaukee with his wife and five children.