Via WPAToday, YouTube: “During the New Deal era, tens of thousands of Indians enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps. This brief film clip shows some of their work. The clip is from a longer film created by the U.S. Department of the Interior, and is provided courtesy of the National Archives.”

Blog by Ashley McNeil, Communications Assistant, The Corps Network

Created during the Great Depression, a time when the United States faced grave economic peril, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a federal work relief program that, from 1933 until 1942, put 3 million unemployed young men to work building and restoring America’s natural resource infrastructure.

Though the CCC was intended to provide stability and a new beginning for its participants, the benefits of the program were not equally distributed among all populations; the main beneficiaries were white enrollees. As detailed in a previous blog, the CCC failed to live up to its promise to provide equitable work and training opportunities to African American Corpsmembers. Many African Americans faced hostility from white supervisors, or were forced to serve in black-only camps, where conditions were poor. For Native Americans, however the federal work relief experience was quite different.

Technically, most Native Americans did not serve in the CCC, but rather in a parallel program. In 1933, not long after the formation of the CCC, the Indian Emergency Conservation Work (IECW) program was created at the request of John Collier, Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). It was Collier’s hope that work relief projects, like those performed by the CCC, could benefit reservations. Pressure to create a separate program came from Native Americans and the BIA, who objected to having the standard military-style CCC camps on tribal land.

Technically, most Native Americans did not serve in the CCC, but rather in a parallel program. In 1933, not long after the formation of the CCC, the Indian Emergency Conservation Work (IECW) program was created at the request of John Collier, Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). It was Collier’s hope that work relief projects, like those performed by the CCC, could benefit reservations. Pressure to create a separate program came from Native Americans and the BIA, who objected to having the standard military-style CCC camps on tribal land.

President Franklin Roosevelt initially approved $5,875,200 in funding for the IECW, which, by executive law, was renamed the Civilian Conservation Corps Indian Division (CCC-ID) in 1937. The program was focused on “Indian work”: employing Native Americans on federally recognized reservations with a goal of preserving tribal lands and promoting sustainable ranching and farming. Projects involved road construction, erosion control, reforestation, and water resource development.

Records indicate 80,000 – 85,000 men served in the CCC-ID during the years of the Depression. Outside of work on reservations, the CCC-ID built dams, roads, trails, and fences on land near reservations. Native Americans received training in gardening, animal husbandry, safety practices, and academic subjects. As stated by political columnist Albert Bender in the article “History shows that joblessness among Native Americans can be lowered,” “The Indian Division produced awesome results. To cite only a few, reservation forests had 9,739 miles of truck trails laid out; 1,351,870 acres put under pest control; and countless fire lookout towers constructed. Indian grazing and farm lands had 263,129 acres subject to poisonous weed eradication, and 1,792 large dams and reservoirs were constructed.” Some of these accomplishments are still visible to this day.

While day-to-day operations at CCC camps were largely managed by the military, the BIA and tribal governments, or “agencies,” oversaw the CCC-ID. For example, branches of the CCC-ID were overseen by the Crow Agency of Montana, the Northern Cheyenne Agency of Montana, the Flathead Agency of Montana, the Turtle Mountain Chippewa of North Dakota, and the Sioux of South Dakota.

The CCC-ID was one part of what would be the called the “Indian New Deal.” In 1934, John Collier encouraged President Roosevelt to sign into law the Wheeler-Howard Act, otherwise known as the Indian Reorganization Act. This legislation reversed harsh restrictions enacted through the Dawes Act of 1887, which had authorized the federal government to assimilate and strip Native Americans of their culture and claim 90 million acres of tribal land.

Under Wheeler-Howard, Native Americans could purchase new land. Additionally, the government recognized tribal institutions and repealed prohibitions on Native language and customs. In conjunction with this legislation, the CCC-ID was the first measure to bring material aid to reservations, encouraged self-administration by Native Americans, conserved tribal land resources, and employed thousands of Native men.

As Collier said, the CCC-ID was, “the greatest opportunity and the greatest challenge confronting the Indian Service and the Indian tribes.” In simple terms, this was the first time the federal government allowed Native Americans to, at least to some extent, hold the reigns. Collier went on to state, “No previous undertaking in Indian Service, has so largely been the Indians’ own undertaking.”

Once the CCC-ID received funding, the program grew quickly. Within six months of its inception, 72 camps were present on 33 reservations in 28 states. The CCC-ID received more applicants than anticipated. To accommodate this, officials staggered employment of enrollees and allowed them to work on neighboring reservations only if it was approved by tribal council.

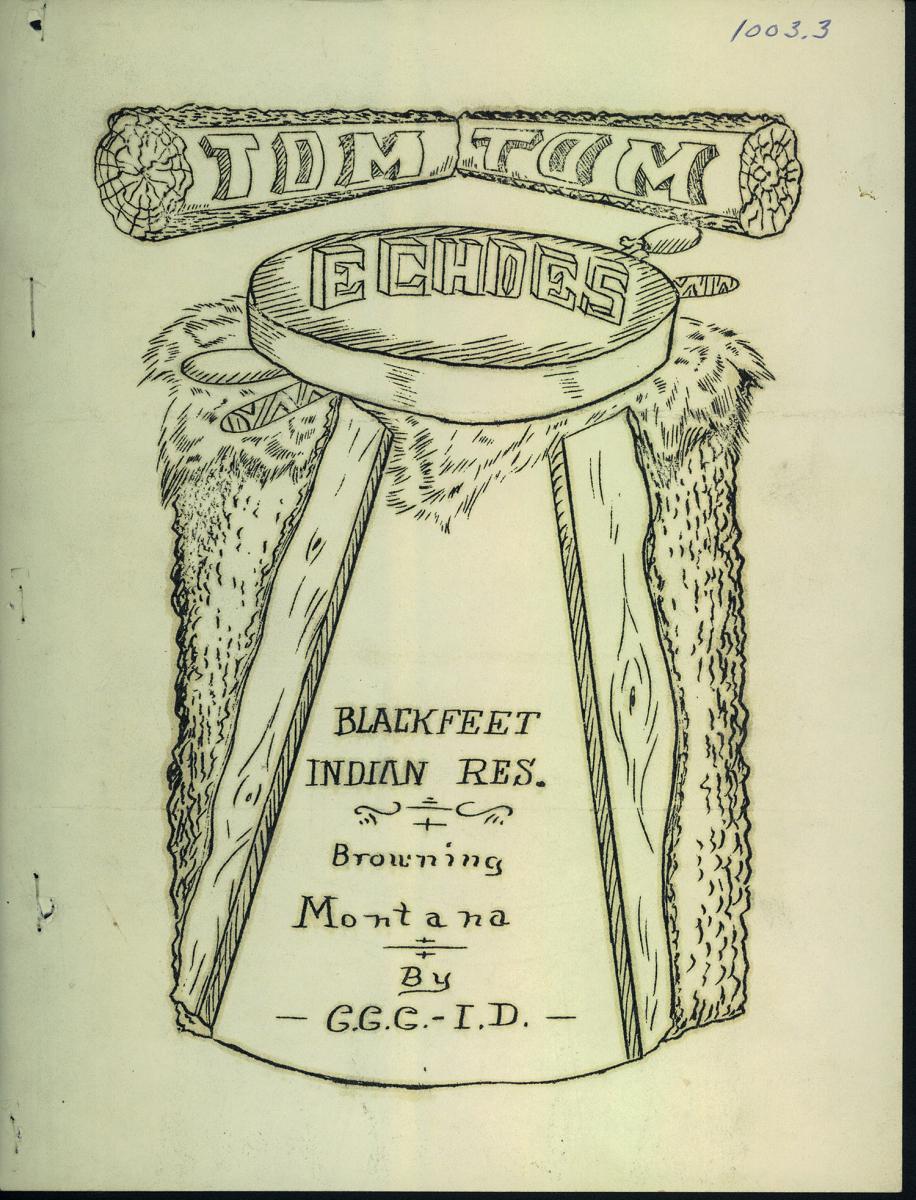

With assistance from the BIA, tribal councils oversaw CCC-ID camp enrollment, structure, and projects. Because of this, records of enrollees were processed differently, with some tribal governments collecting more data than others. Many tribes created narrative reports detailing work completed by enrollees. Some tribes opted to publish information about their work in their own newsletters, such as the Shoshone Tattler and the Blackfeet Tom Tom Echoes. These publications featured anecdotal history, as well as jokes, stories, and drawings from corpsmen.

With assistance from the BIA, tribal councils oversaw CCC-ID camp enrollment, structure, and projects. Because of this, records of enrollees were processed differently, with some tribal governments collecting more data than others. Many tribes created narrative reports detailing work completed by enrollees. Some tribes opted to publish information about their work in their own newsletters, such as the Shoshone Tattler and the Blackfeet Tom Tom Echoes. These publications featured anecdotal history, as well as jokes, stories, and drawings from corpsmen.

One notable source that discussed Native contributions was, Indians at Work. This monthly publication, produced by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), contained articles, photographs and drawings of Native Americans, reservation life, and western scenes that helped promote the accomplishments of Native corpsmen.

Besides its management structure, the CCC-ID program differed from the CCC in many ways, including such elements as age restriction, living arrangements and wages. The CCC only enrolled men between the ages of 18 and 25. The average age of Native American corpsmen was 34; 172 enrollees were over the age of 35, and three were over the age of 75.

While CCC camps employed 200 men for six-month terms, only 40 to 50 Native Americans worked in units together. Also, as opposed to the traditional camp-setting, Native corpsmen lived in one of three types of domiciles: the permanent boarding camp for single men; the home camp for those wishing to live at home; and the family camp for projects of short duration where the entire household could reside temporarily in tents (another difference about the CCC-ID was that married men could serve). African American and white corpsmen did not have these housing options.

The basic wage for CCC-ID members was $30.00 for twenty workdays a month, or $1.50 per day, plus a 60 cent-per-day subsidy for those living at home. Enrollees also received from $1.00 to $2.00 per day for use of their own teams of horses. For those who lived at home, their pay was $2.10 per day for not more than twenty days in any one month, a possible total of $42.00 per month. In comparison, white and African American corpsmen earned a flat $30.00 per month, $25 of which had to be sent home to their families.

While the CCC-ID had what could be considered advantages over the CCC, there were some downsides. For instance, some living conditions were unsanitary. In all, however, the CCC-ID was more flexible than the CCC. It had less militarily structure and focused primarily on the goals of the Wheeler-Howard Act and improving Native American self-sufficiency.

The CCC and CCC-ID came to an end in 1942 when, as the U.S. joined WWII, Congress rejected funds to continue programming. For Native Americans, the CCC-ID was progressive in many ways. Native peoples reclaimed aspects of their culture, gained new educational and agricultural skills, and saw employment opportunities. The end of the CCC was arguably a setback; the program was important to Native Americans because one of their most valuable resources – their land – was cultivated, and small parts were returned to them. Collier stated, “The ending of CCC…is a heavy, heavy blow to Indian Service, to the Indians, and to social policy in the United States. It is just that: a heavy and undeserved blow.”

For your consideration

As you read this blog, here are some questions for you to consider:

- The CCC and CCC-ID were disbanded in the early 1940s as the country turned its attention to WWII. John Collier described the end of the CCC-ID as a “heavy and undeserved blow.” Do you agree with his statement? If the CCC-ID program had continued (or possibly still functioned to this day), how do you think it would have influenced Native communities culturally? Economically? Socially?

- The Smithsonian Libraries website offers the opportunity to read old copies of Indians at Work, the Bureau of Indian Affairs publication from the ‘30s and ‘40s. What do you learn from these publications? What do you not learn?

- After decades of stripping Native peoples of their land and culture, the federal government gave tribal leadership a degree of agency over the CCC-ID program. How do you think tribal governments felt about this?

- It has been over 80 years since passage of the Wheeler-Howard Act, or “Indian New Deal.” However, as stated by the National Congress of American Indians, “Tribal communities are among the poorest in the country and unemployment rates in Indian Country often stand above 50 percent.” What do you believe the federal government should do to address these ongoing issues?

- What can land management agencies do to better share the history and accomplishments of Native Americans on lands that are now national parks, national forests and other public spaces?

- For Corps: Do you engage Native American youth in your programs or offer programming specifically for Native youth? If so, how is programming for Native youth different? How might any specialized education and activities offered in Native American programs also benefit non-Native Corpsmembers?

- If your Corps does not actively engage Native American youth, what steps can you take to better engage Native populations in your region?

Resources

These resources, and much more, can be found in the Moving Forward Initiative resource library.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Indian Reorganization Act.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 10 October 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Indian-Reorganization-Act

Bender, Albert. “History shows that joblessness among Native Americans can be lowered. People’s World. 22 September 2014. https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/history-shows-that-joblessness-among-native-americans-can-be-lowered/

“Native Americans.” Digital History, 2016. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3449

White, Cody. “The CCC Indian Division.” Prologue Magazine. Vol.48, No.2. 2016. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2016/summer/ccc-id.html

Gower, Calvin W. “The CCC Indian Division: Aid for depressed Americans, 1933-1942.” Minnesota Historical Society. https://corpsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/v43i01p003-013.pdf

Bromert, Roger. “The Sioux and the Indian-CCC.” South Dakota State Historical Society. 1978. https://corpsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/vol-08-no-4-the-sioux-and-the-indian-ccc.pdf

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Dawes General AllotmentAct.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 12 December 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dawes-General-Allotment-Act

McLerran, Jennifer. “A New Deal for Native Art: Indian Arts and Federal Policy 1933-1943.” The University of Arizona Press 2012. https://bit.ly/2pT07jI

Bureau of Indian Affairs. “Indians at Work.” 1933 Bureau of Indian Affairs. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/indians-work

WPAToday. “The CCC on Indian Reservations.” YouTube, 27 June 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JbKIPSdjlh0.