Article by Ashley McNeil

In 1933, at the peak of the Great Depression, the overall unemployment rate in the United States was well over 20 percent. African Americans were hit hardest, experiencing an unemployment rate two to three times that of white Americans.

In these desperate times, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC): a federal work relief program that, from 1933 until 1942, put 3 million unemployed young men to work building and restoring America’s natural resource infrastructure. In exchange for their labor, corpsmen received $1-per-day, regular meals, housing, and access to education. Though the CCC disbanded when the US entered World War II, its model lives on in more than 130 modern Corps across the country, most of which are managed by nonprofits or units of state or local government.

The CCC was created with progressive intentions. With persuasion from Oscar DePriest, an Illinois representative and the only Black member of Congress, the legislation that established the CCC included language forbidding discriminatory practices based on “race, color, or creed.”

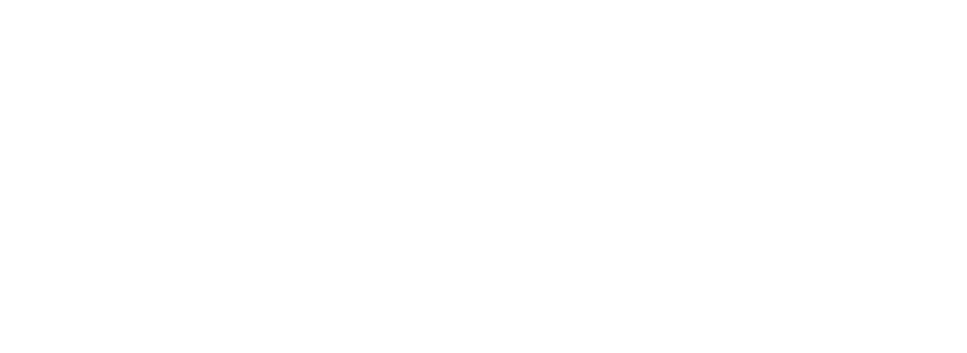

Throughout the years of the program, more than 200,000 African Americans and 80,000 Native Americans served in the program. However, their experience was, in many cases, markedly different from that of their white peers. Under the argument that “segregation is not discrimination,” the CCC failed at its promise of inclusivity.

The CCC existed during the era of Jim Crow segregation. Though CCC camps were, at least in the beginning, supposed to be integrated, this largely only happened in areas where the African American population was not large enough to warrant a separate camp. To reduce community outcry, many of the 150 African American CCC camps were built on remote federal lands, away from the public.

In 1934, Robert Fechner, Director of the CCC, ordered the Army to review national practices around African American enrollment. Contradicting the Army’s conclusion that the CCC should not enforce segregation, as this would exacerbate the problem of finding locations for camps that served only Black corpsmen, Fechner issued an order in 1935 to make the “complete segregation of colored and white enrollees” the rule.When questioned about this action by the NAACP, Fechner wrote.

“I am satisfied that the negro enrollees themselves prefer to be in companies composed exclusively of their own race…This segregation is not discrimination and cannot be so construed. The negro companies are assigned to the same types of work, have identical equipment, are served the same food, and have the same quarters as white enrollees.”

Picture from Digital Public Library of America

To appease citizens concerned about the placement of all-Black camps in their communities, only white supervisors were put in charge of such camps, leaving Black corpsmen little opportunity for advancement. President Roosevelt suggested this practice be relaxed to allow a few token “colored foremen,” and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes was vehemently opposed to Fechner’s racist policies against having African Americans in leadership roles. However, pushback from communities and legislators, as well as Fechner’s beliefs and prevailing discriminatory practices meant that African American corpsmen generally did not have the same upward mobility as white corpsmen.

Meanwhile, Native Americans almost exclusively served on reservations in programs operated in collaboration with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Critical infrastructure improvements were needed on reservations, and tribal leaders in fact had quite a bit of say in which projects were completed. There is limited literature on corpsmen from other non-white racial and ethnic groups participating in the CCC, but many Hispanic and Latino men certainly participated, especially in the American Southwest.*

African American enrollment in the CCC was capped at 10 percent, reflecting the racial profile of the national population, but this ignored the fact that African Americans faced disproportionately worse economic situations than white applicants. Despite the CCC’s founding language barring discrimination, qualified African American applicants were frequently turned away. When hired, they often faced hostile work environments. This included racial slurs and jokes, forcing Black corpsmen to the back of the line, and giving them the least desirable quarters and equipment. Certainly reprehensible, these aggressions were unfortunately common in society at the time. However, there were more extreme cases of racism, including one account of an African American corpsmen being discharged from a camp in New Jersey for refusing to fan flies from a white officer.

CCC camps in some Southern states initially outright denied African Americans under the argument they were needed to tend fields. John de la Perriere, the Georgia director of the CCC, stated all applicants in Clarke County be “classed A, B and C” based on need. However, all non-white applicants fell into classes B and C and were far less likely to be recruited. In Florida, state director John C. Huskisson agreed, when pressured by the federal government, to “lower his standards” enough to accommodate two hundred Black corpsmen.

Despite Fechner’s segregation order, some camps remained integrated, particularly in the North and in regions with smaller African American populations. Fechner allowed this “because of the natural adaptability of Negroes to serve as cooks.” In some integrated camps, African American corpsmen were indeed assigned kitchen duties as opposed to more technical work outdoors. Also, contrary to Fechner’s claims that African American camps completed the same projects as white camps, there are accounts that Black camps in some regions only did routine work and were not assigned special or priority projects.

Picture from Oregon State University Special Collections and Archives.

Despite this, it is undeniable that African American corpsmen played a significant role in conservation efforts and the development of our nation’s public lands. Aspects of the CCC were certainly discriminatory, but, as stated by historian John Salmond in his book on the CCC, “to look at the place of the Negro in the CCC purely from the viewpoint of opportunities missed, or ideals compromised, is to neglect much of the positive achievement.”

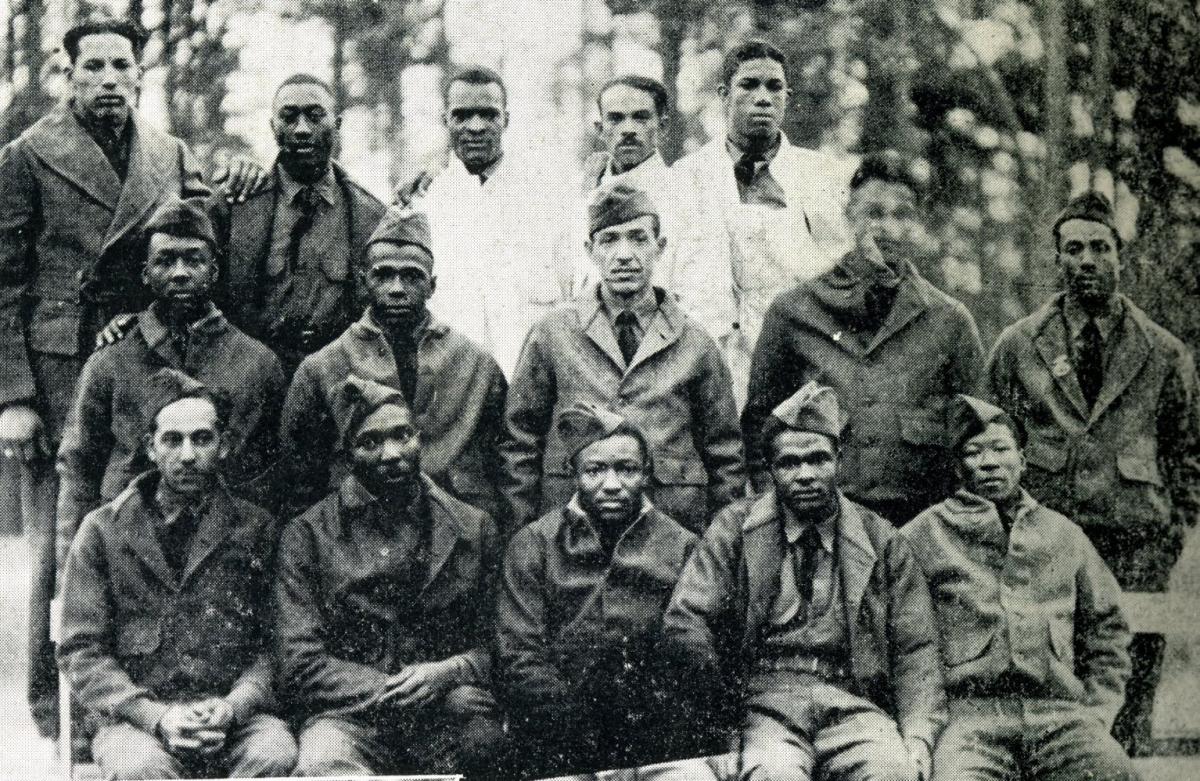

Black corpsmen did ultimately gain much needed financial assistance through their service, and tens of thousands of African American corpsmen participated in educational programming from the elementary to college level. There are countless anecdotal reports from African American corpsmen who were grateful for the opportunity to learn and work in the CCC.

To this day, however, the more than 200,000 Black corpsmen of the CCC remain “hidden figures” in the development of our nation’s public lands. Most African American corpsmen were from cities where the forestry and conservation skills they learned in the CCC were not applicable. As Dr. Olen Cole, Jr. states, this work “must have seemed artificial and impractical- or at the very least, to have little relevance to their past and future lives.” Many CCC members went on to “negro jobs” as chauffeurs, cooks and gardeners. Many desirable public lands jobs were not, at the time, open to Black men, or were more likely to go to white applicants.

As Cole states, the CCC had little lasting impression on the way African American corpsmen felt about the outdoors. It was merely a temporary way to make money, not prepare for a career.

“This failure, critical then, remains a failure of many environmental organizations today.”

*More to come on this topic – including the experience of Native American, Hispanic and Latino men in the CCC – in future blogs.

Please find a list of resources used for this blog on the Moving Forward Initiative homepage.

For your Consideration:

As you read this blog, here are some questions for you to consider:

- What do the policies of the CCC tell us about how the federal government viewed racial discrimination at this time?

- As some historians state, the CCC’s work opportunities seemed irrelevant to African American corpsmen who mainly lived in urban centers. How might this relate to the problem public lands agencies face today with disproportionately low visitation from persons of color?

- What can federal resource agencies do today to increase the presence of people of color visiting and working on public lands?

- Read this firsthand account from Luther Wandall, an African American member of the CCC. What was positive and negative about his experience? How do his remarks make you feel?

- For Corps: What measures have you taken (or can you take) to increase the presence of people of color in administrative or leadership roles in your organization?

- For Corps: How do you conduct outreach in your community to people of color? Have your ideas been accepted? Do you believe the information you provide is culturally relevant?

- For Corps: Have your Corpsmembers ever experienced any racially-motivated hostility in the communities where they work?

- How can this be combated? What conversations do you have with Corpsmembers in the event racism, hostility, or discrimination on the job occurs?