This week is the inaugural article in a new series of interviews with Corps Staff members.

This week is the inaugural article in a new series of interviews with Corps Staff members.

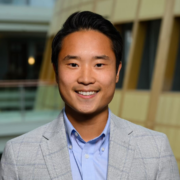

Michael Muckle is the Director of the New Jersey Youth Corps of Phillipsburg and talks about his experience working at the Corps, advice from mentors, and what inspires him.

1. What are some of the projects that your Corps is working on right now that excite you the most?

There’s a few things here in New Jersey that we’re currently working on that I’m excited about:

a. Our upcoming HOPE project at the Gateway National Recreation Area @Sandy Hook is something that I’m really anticipating because it will give our Corpsmembers such a unique opportunity to learn preservation craft skills while rehabilitating a historic building in a really beautiful setting.

b. The second project I’m excited about is developing a partnership with the American Conservation Experience (ACE) to put our Waders in the Water trained Corpsmembers to work here in New Jersey. ACE has taken the lead on some riparian restoration projects in the mitigation banking arena here in the state and we look to partner with them to place our Youth Corps WitW Level 1 Corpsmembers on site with them.

c. The third ‘project’ I’m excited about is helping the state of New Jersey develop its implementation plan for the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. We believe that WIOA will enable us to implement new ideas and programmatic strategies on a local level to expand and lengthen the services to our Corpsmember participants – who are requiring more effort and more time to achieve certain goals within Youth Corps. It’s an opportunity to amend our programs with opportunity to increase the quality of service for the next decade…maybe longer. That’s exciting.

2. What kinds of careers are typically available in your neck of the woods for Corpsmembers?

Jobs usually available for our Corpsmembers are found in retail, foodservice and warehouse work given our rural location here in New Jersey. Other typical placements are entering into Community College, or directly into military service.

Here at our program we’re trying to change the mindset of Corpsmembers by offering them unique service opportunities that shadow careers within the field of public service. In doing so, we hope to reveal what’s possible to the Corpsmembers by introducing them to people in the field that have themselves blazed an unconventional career pathway. That one-on-one interaction is essential to the building of confidence and gaining of trust on behalf of the Corpsmember. When they see that others like themselves can achieve, they buy into the idea and start to believe.

3. What are some of the most typical problems you face when working with Corpsmembers, and how do you solve them?

I thought hard about this question. ‘Typical’ problems working in Youth Corps, as most readers might guess, are anything but typical. On any given day, we encounter myriad problems ranging from the relatively benign like punctuality and attendance to the more serious and detrimental behavioral issues – drug addiction, sexual abuse, gang involvement, etc. The stories of our Corpsmembers are as dramatic as they are varied. We approach all these issues from a position of patience and understanding while utilizing our entire staff in addressing an individuals’ needs. We’re all about second chances. It is challenging, exhausting and exhilarating all at the same time. It’s particularly satisfying when a young adult has an epiphany about his or her life and then decides on an action of assuming responsibility for their future. It’s all worth it in the end!

4. What’s something about your organizational culture that you are proud of and something you want to improve?

There are two things in particular I’m proud of relative to the organizational culture here at the Phillipsburg Youth Corps. First, I’m proud of the legacy of service this program has provided to this community. Our seventeen years here haven’t been easy. We’ve had ups and downs, but we’ve had a lot of help from a lot of people. I think that we’ve become an essential part of this community here in Phillipsburg and Warren County. We’re very proud of that.

The second would be the level of commitment and passion for the youth we serve on behalf of my staff. Their hard work and determination are so inspiring! They have a familial approach in everything they do, are wonderful mentors to the young adults they work with and are the most patient people I know. They propel me to want to do better…for them and our youth.

Something I would like to improve is to become more effective with communication; things develop and change so quickly over the course of a day sometimes, and it is difficult to be able to keep pace and inform everyone about those developments. Getting your message out to the right people is so essential to finding partners that support your program as well as identifying the youth we serve, and with so many systems to do so (i.e. Social media, websites, newsletters, etc.), your message can get muddled in the medium you choose. I’d look to improve upon that.

5. What’s your favorite kind of terrain and why (Beach, mountain, forest, lake, tundra, etc…)?

This is an interesting question, but I’m going to answer it like a politician, so I apologize beforehand. I just love the natural world. I can’t pick one type of terrain or environment over another because I feel just as comfortable down the shore as I feel up in the mountains. I have a deep fascination and appreciation of both and everything in between, which by the way, is why I love New Jersey. I’m originally from Connecticut and I had the impression that most people who travel through New Jersey are only familiar with; the industrial I-95/Route 1/NJ Turnpike corridor. But the best of New Jersey is just beyond all that you can see when you’re barreling down the NJ Turnpike. New Jersey has it all. Mountains, forests, farms, beaches…it’s perfect.

6. What’s something accessible to the masses (a movie, tv show, song, book, event) that has inspired or influenced you recently?

Anyone who knows me knows that this is almost impossible for me to answer efficiently or succinctly, but I’ll try. One is a song, and it’s not even a new song, but Ben Harper’s “With My Own Two Hands” from 2003 is a personal anthem of mine. One of my former students turned me on to it, and from first listen, it spoke to me. It embodies an ethos of service with an infectious reggae hook. It reminds me why I joined AmeriCorps in the first place in 1998 and cements my resolve as I continue to serve alongside our Corpsmembers. Good stuff.

The second is a book I’m just getting into by Robert Putnam called “Our Kids: the American Dream in Crisis.” It’s a study on the growing inequalities in America and how it is affecting our youth. I’m hoping it might open my eyes to something so it can foster a constructive conversation among our youth. It is interesting so far.

7. What’s one of the best pieces of advice a mentor has given you?

One thing the person who had my job before me said as they pulled me aside while walking out the door for the last time was “Seek balance, Mike. You’ve got to seek balance in all you do.” That has stayed with me ever since. It was a tough time of transition for me, both personally and professionally. I was working long hours, so I understood where the advice was coming from, but still I didn’t heed it. It took a few years to fully comprehend and implement that philosophy, and I still struggle most days – but putting emphasis on the things that bring me the most satisfaction – my wife, my daughter and our family – has helped me.

This week is the inaugural article in a new series of interviews with Corps Staff members.

This week is the inaugural article in a new series of interviews with Corps Staff members.

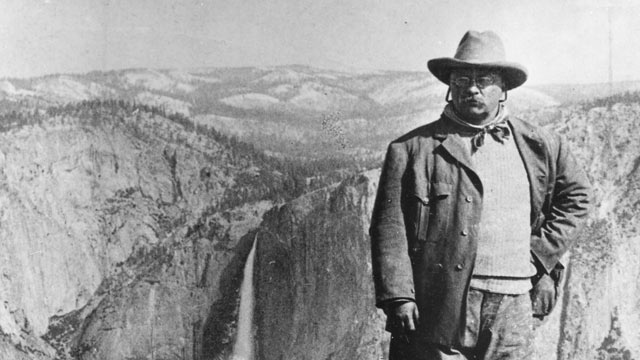

“A true conservationist is a man who knows that the world is not given by his fathers, but borrowed from his children.”

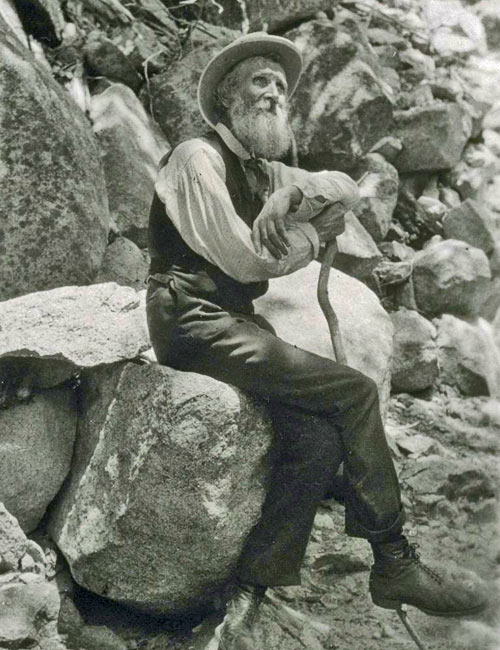

“A true conservationist is a man who knows that the world is not given by his fathers, but borrowed from his children.” “Until you dig a hole, you plant a tree, you water it and make it survive, you haven’t done a thing. You are just talking.”

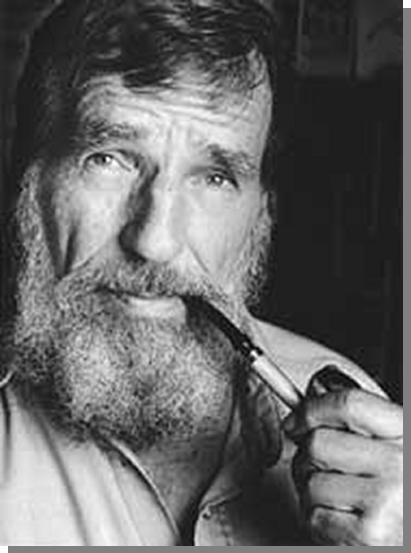

“Until you dig a hole, you plant a tree, you water it and make it survive, you haven’t done a thing. You are just talking.” “To be whole. To be complete. Wildness reminds us what it means to be human, what we are connected to rather than what we are separate from.”

“To be whole. To be complete. Wildness reminds us what it means to be human, what we are connected to rather than what we are separate from.” “May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds. May your rivers flow without end, meandering through pastoral valleys tinkling with bells, past temples and castles and poets’ towers into a dark primeval forest where tigers belch and monkeys howl, through miasmal and mysterious swamps and down into a desert of red rock, blue mesas, domes and pinnacles and grottos of endless stone, and down again into a deep vast ancient unknown chasm where bars of sunlight blaze on profiled cliffs, where deer walk across the white sand beaches, where storms come and go as lightning clangs upon the high crags, where something strange and more beautiful and more full of wonder than your deepest dreams waits for you — beyond that next turning of the canyon walls.”

“May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds. May your rivers flow without end, meandering through pastoral valleys tinkling with bells, past temples and castles and poets’ towers into a dark primeval forest where tigers belch and monkeys howl, through miasmal and mysterious swamps and down into a desert of red rock, blue mesas, domes and pinnacles and grottos of endless stone, and down again into a deep vast ancient unknown chasm where bars of sunlight blaze on profiled cliffs, where deer walk across the white sand beaches, where storms come and go as lightning clangs upon the high crags, where something strange and more beautiful and more full of wonder than your deepest dreams waits for you — beyond that next turning of the canyon walls.” “

“

Let the rain kiss you. Let the rain beat upon your head with silver liquid drops. Let the rain sing you a lullaby.

Let the rain kiss you. Let the rain beat upon your head with silver liquid drops. Let the rain sing you a lullaby.  You are capable of more than you know. Choose a goal that seems right for you and strive to be the best, however hard the path. Aim high. Behave honorably. Prepare to be alone at times, and to endure failure. Persist! The world needs all you can give.

You are capable of more than you know. Choose a goal that seems right for you and strive to be the best, however hard the path. Aim high. Behave honorably. Prepare to be alone at times, and to endure failure. Persist! The world needs all you can give.