Katie Thornton is a storyteller. As a Fulbright–National Geographic Digital Storytelling Fellow, Katie helped create an educational module about audio storytelling for National Geographic’s Storytelling for Impact program. Launched in October 2020, Storytelling for Impact is an initiative to “bring creative storytelling into the classroom” through a series of free, online courses on different mediums of storytelling, including audio, photography, video and graphics. The program is targeted at educators and learners ages 16 – 25.

For the audio storytelling module, Katie examined the history and legacy of segregation in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) of the Great Depression. In the story she developed for the class, Katie speaks with a historian, a descendent of a Black CCC enrollee, and with Capri St. Vil, Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at The Corps Network. We encourage Corps, Corpsmembers, and our partners to learn more about this free, self-paced educational opportunity.

We chatted with Katie about the basics of audio storytelling, her interest in exploring racial equity in the CCC, and about the power of stories to transport us and change our perspectives. Learn more about Katie at itskatiethornton.com.

Banner Image: Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Company 1728. Minnesota Historical Society.

1. Some of our audience might see this conversation and wonder, “how do I become a ‘storyteller’?” Can you talk to us about your journey?

My experience comes from listening to the radio. To me, the first step in telling stories is listening to other people. I was lucky to grow up in Minneapolis, where we have a vibrant radio dial. I could tune to so many different public and commercial stations and hear a variety of experiences and interpretations.

I was drawn to community radio in particular because there are relatively few barriers to entry. It’s affordable and accessible to produce and consume. I was drawn to community radio for its potential to be a hub for very diverse stories.

When I was a teenager, I started volunteering at a community radio station that I later worked at after college here in Minneapolis. Slowly, after hearing people share their stories through community radio and audio, I started to do that myself. Part of why I love podcasting is because it has even less barriers to entry than a medium like radio.

Civilian Conservation Corps fire fighters, northern Minnesota. Minnesota Historical Society. https://bit.ly/3vdTzwI

2. Talk to us about what interested you in telling a story about the Civilian Conservation Corps. In particular, what interested you in exploring the topic of racial equity in the CCC?

In addition to being passionate about radio, I also love public history. I learned later in life that I love history. I didn’t enjoy it in high school. A lot of mainstream history we learn is narrow. The dominant narratives are one-sided, one-dimensional, white-washed. There is a lot more complexity, joy and pain within histories that are more complete. I grew to love history in college because I could learn about the variety of stories in my own state of Minnesota and beyond.

A number of years back, I was doing public history research and came across a resource of assembled headlines, spanning back into the late 1800s, from many of the Twin Cities’ Black newspapers.

I remember continuing to see headlines about Black CCC enrollees fighting to remain in Minnesota. There were stories about how all-Black CCC companies received vile pushback from white Minnesotans. It struck me because I had been passively aware of the CCC, but I had never heard about this history specifically.

I’ve wanted to cover this story for many years, but, as more people began to advocate for a modern federal Corps program, I thought it was especially important to share this history now. I wanted to look at how there was racism both on the books and off the books that led to this inequity. I wanted to show that a lot of the inequity of the original program was due to de facto racism and white backlash and the government’s willingness to cave to it.

That story was important to me because I had known about the CCC for a long time, but I had never heard that there were many white Minnesotans who protested virulently and were so upset that they pushed an all-Black camp out of our state. If we want to celebrate this program, we also need to be honest about the inequity. We still live with a lot of inequity and white backlash today. Just having racist laws off the books, at least explicitly, doesn’t mean a new CCC program will be extended equitably.

3. How did you identify the subjects you interviewed for this project?

When I start any project, I try to educate myself. I respect that I’m not the expert. When someone is willing to do an interview, I want to be sure I’m not taking their time and asking them to explain things I could’ve learned through what they’ve already made public.

For this story, I came across so many wonderful people I wanted to interview. With an audio story – especially one that’s historically focused – I like to find someone who’s a historical expert. I also love to talk to someone who has a direct personal connection to the story; otherwise, it’s another history that doesn’t have that personal representation. And then I also like to find someone in the present who’s looking to the future. And that’s where you came in, Capri.

I found a bunch of people who had written about CCC history, and specifically about Black and Indigenous enrollees and the institutional racism they faced. I ended up speaking with a Minnesotan historian. She was an oral historian who, decades prior, had the opportunity to speak with many, many enrollees of different races who had been active in Minnesota.

As mentioned, I also wanted to bring that personal story, which allows you to understand how big histories played out in the lives of individuals. I came across Dr. Cheryl Kirk-Duggan. She was researching her father’s time in the CCC and had posted on a history and genealogy blog. This was me deep in the internet scroll. I cold-emailed her and asked if she’d be willing to talk. Very generously, she got back to me. She had gotten her father’s records from the CCC and we were able to go through them over Zoom. It was just amazing – her father was an amazing person.

As an aside, this is how I contact most people I feature in a story. It’s just cold-calls, cold-emails. I am repeatedly surprised by peoples’ willingness to chat. Not everyone says yes, but if you take the time to educate yourself and demonstrate that you’re prepared and you want to be a steward of someone else’s story – I’ve been blown away by peoples’ generosity and willingness to share.

Lastly, I wanted to talk to someone who is working towards the future and can shed light not just on the history, but what the legacy is in the present and how current Corps programs can, and are, pushing back against that legacy. I came across The Corps Network and Capri’s work. To me, it was really important to show that not only did this happen in history, but there are people actively working to make this a more equitable space in the present. Especially as we look to expand Corps programs, we need to learn from those who are already doing the work.

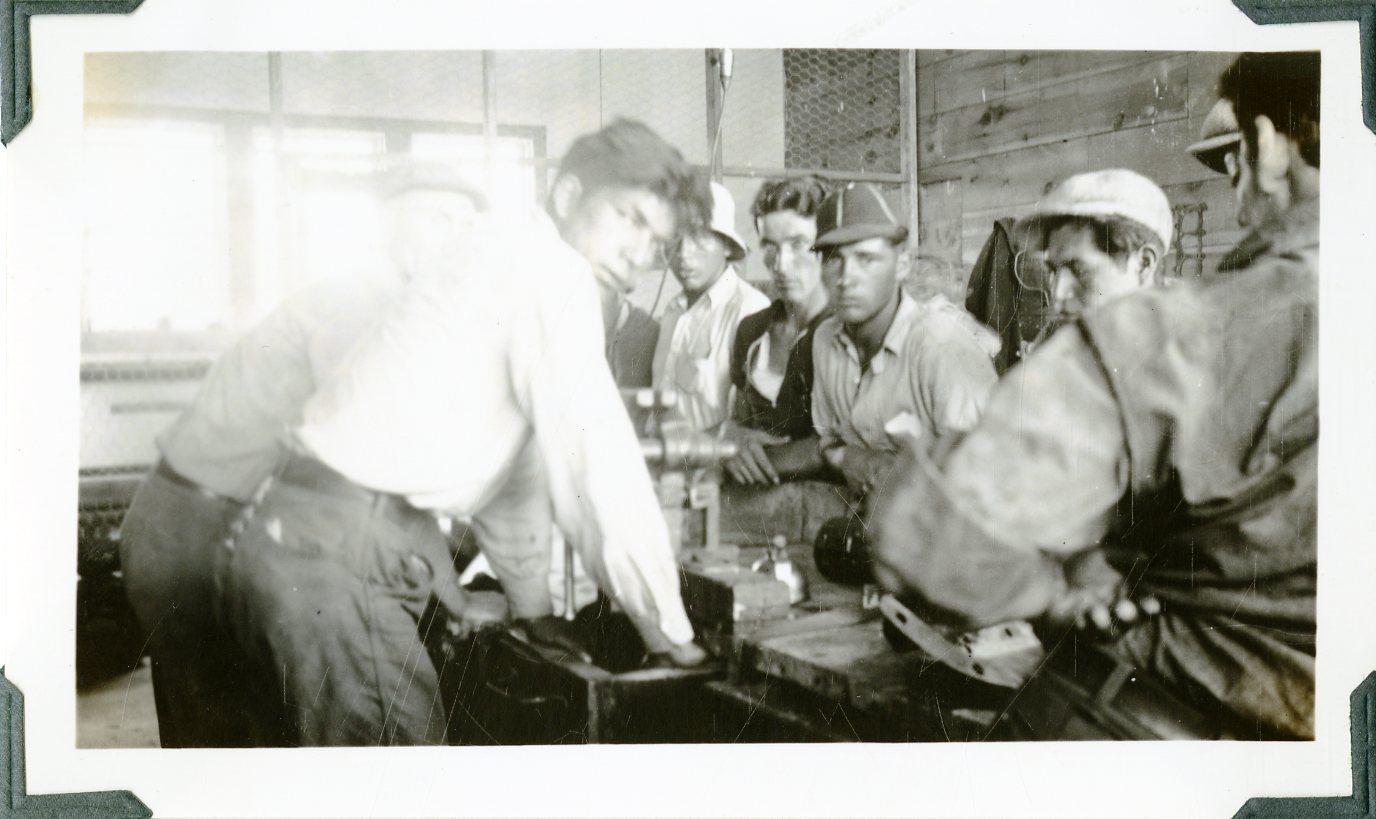

Mechanics Class. CCC-Indian Division Camp, Red Lake Agency, Minnesota. National Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/76048033

4. The module provides an overview of how to build an audio story. For those who don’t know, could you briefly talk about the process of creating an audio story? Are there any special techniques you have to use?

To give a broad overview, always start with research and showing up prepared to talk to people.

Once I’ve done the research, I create a rough outline of how I think the story will go. I remind myself that what I think know, filtered through my lens, is going to change once I get into the interviews.

Then I identify people to talk to. At this point, I also identify other sound I can imagine bringing into the story. I can’t use historic images, so how do I set the scene and tell the story in sound? Can I get archival audio? In this piece, I have part of a speech that FDR gave about the Civilian Conservation Corps. There are also natural sounds. If I’m describing a place in Northern Minnesota, can I go there and capture what it sounds like today? (For the audio story created for this project, Katie visited the site of a former CCC camp in Northern Minnesota)

Then I conduct interviews. I prepare questions, but I also ensure I let the conversation flow based on where the interviewee and their expertise wants to bring it. I then transcribe those interviews and revise my outline with what I now know. I usually take the most powerful quotes from the interviews and slot them into the outline where I think they’ll fit. Then I begin to write the story around them. Ultimately, I want to be a guide: I want the voices of the people I interview to be the most prominent.

Then it’s a matter of recording narration and editing audio. You can find free or very cheap audio editing software online.

Then I give it a rest. I listen again. I get feedback and I make revisions. Something I talk about in the class, but that I want to reiterate here, is that there’s so much great work you can do with your phone. That’s a really powerful tool. If you have a smartphone and can even just go under a blanket, you can record decent-quality audio.

If someone is interested in getting a feel for how to put together an audio story, something I’d recommend is to listen really keenly. As you’re going about your day, start thinking, “if I couldn’t use visuals, how would I describe my surroundings right now? How would I bring it to life? Would there be cars going by? Would there be birds chirping? Would there be water boiling on the stove?” As you think of those things, record them into your phone.

Once you start to get a sense of how to bring stories to life with audio, you can do fun little experiments on your own. You can try to paint a landscape using only sound.

5. Different generations seem to have different preferences for how they consume media. Many young people might listen to podcasts, but do not personally have experience producing audio content. Can you talk to us about why you believe audio storytelling is a medium that students should consider?

-

-

What is unique about audio storytelling? Where do you see it going in the future, particularly in relation to other forms of media, like print or video?

-

With social media we have a lot of practice sharing stories in visual and written formats. We have less experience putting together audio stories. That being said, I think the audio medium is very accessible to produce and consume.

Something about audio is that it can be longform – you can go really in-depth – but it doesn’t require you to sit down and watch a movie for an hour or two. It doesn’t require your full attention. It’s simultaneously very intimate – it’s in your ears, it’s in your living room – but it doesn’t demand all of your focus. What I think is special about audio is that it’s with you; it doesn’t consume you. We’re all busy – I think that’s why podcasting is really growing, both with people listening and producing.

I think people often think people of our generation or younger want things to be short and snappy. I think a lot of young people are longing for longform stories, but they have to be done in a way that’s engaging. Audio can be a simultaneously engaging and freeing medium.

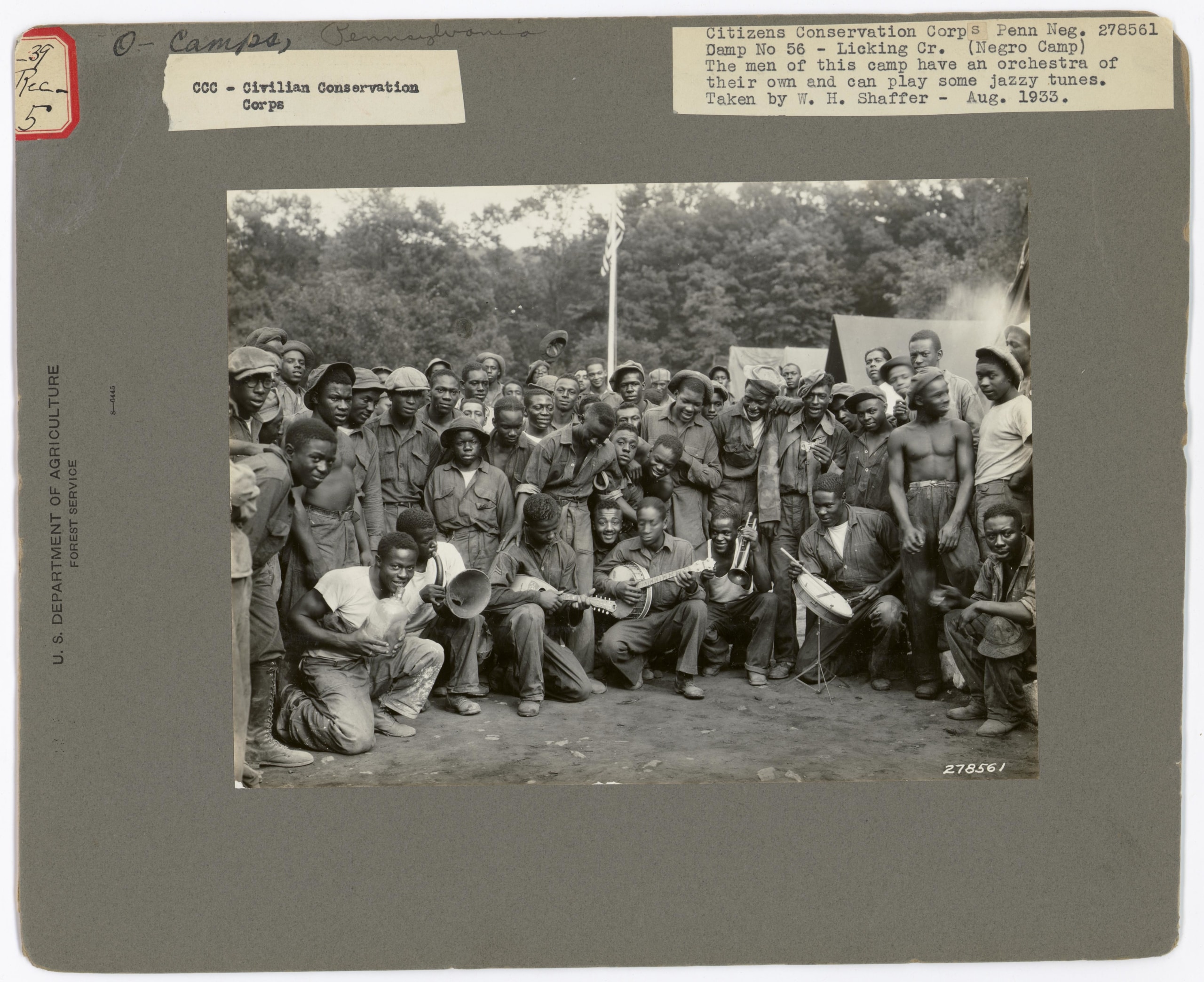

Civilian Conservation Corps Camp No. 56 in Pennsylvania. From the Records of the U.S. Forest Service. National Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7004946

6. What would you to say to a young person who feels like they don’t have a story to share? What would you tell them about what makes a compelling story?

I think everybody has a compelling story to share. Nobody has made it through life without something that has challenged them or thrilled them. Those are what make good stories.

I think it’s also important to remember that you’re an expert in your own experience. That’s an important thing to remember when interviewing someone else, too.

I think that sometimes things that happen to us individually might seem mundane because we lived them or are living with them, but not everybody has the same experiences. Somebody else might find your experiences really fascinating. If you are somebody who has a story with degrees of struggle and you can share that, it might reach somebody who is in a similar situation.

One of the first audio stories I published on a radio station was about living with and managing chronic illness and chronic pain. I got a lot of feedback that I didn’t necessarily expect. People shared with me that hearing someone articulate about it publicly was really powerful for them. Don’t underestimate the stories that you have and the power for them to make a difference for someone else.

Also, if you’re not sharing a personal story, maybe there’s a story in history that you learned that changed a lot about what you thought you knew. Like with me, when I learned this inequitable history in the CCC, I thought it was important for other people in my position who had missed that history to know. If you look for more complex historical stories, you can help other people have that learning moment, too. Even if it’s not a personal story about you, maybe it’s an ah-ha moment and you’re able to share that with other people.

7. These storytelling modules are targeted at educators and people ages 16 – 25. Why – particularly considering the challenges our society has faced over this past year – do you believe it’s important for our society to hear stories told by our young people?

Speaking from my own opinion, I think young people have always been on the forefront of social change. Storytelling can be a massive tool for change. I think it’s very true that a lot of hatred, violence and bigotry comes from not having a personal connection to people. When you know someone, it’s harder to misunderstand. Sometimes, especially if you’re in a geographically isolated area, you might only know these stories of other people if you hear them through a set of headphones or speakers. Storytelling is a really important tool for increasing understanding.

I also think it’s important to note the difference between being reported on and reporting from a community. There’s power in being able to share your own stories. When youth are able to share their own stories, it will give people a more accurate understanding of why social issues are so important to them, why we need to be out in the streets and fighting for change.

Again, I think there’s this wrong perception that young people aren’t interested in longform stories. It’s just that the tools we’ve been given through social media are short-form. To me, I think social media is evidence that young people are hungry to share their own stories. People are hungry to make clear just how things like institutional racism, or social isolation during a pandemic, hit them and drive their experiences. I think the more media young people can use to share their stories, the better.