Blog by Cassandra Ceballos, Programs Assistant, The Corps Network

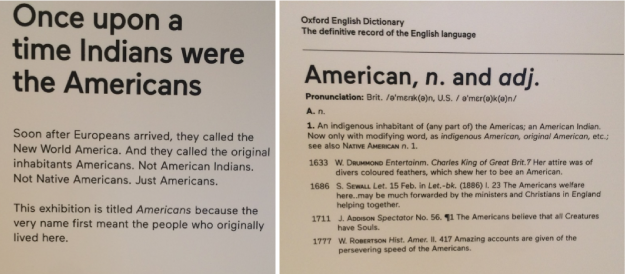

From the Americans exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

On Sunday, February 18, I found myself striding purposefully into the Museum of the American Indian.

Although I’ve lived in D.C. for the past six months, this was my first trip to the museum. Despite my mestizo heritage, I never felt a connection to the curvilinear, limestone building. I’m not alone in this sentiment; fourteen years old, the museum has, as stated in The Washington Post, “struggled to find an audience, and settle on a consistent approach to how it tells stories and presents information.”

Once inside, I ascended the steps of the grand staircase, two at a time, barely able to contain my excitement. The reason for my visit was simple: the Americans exhibit. Unveiled on January 18, 2018, the exhibit will run until January 2022.

The Washington Post calls Americans “an exhibition that examines how images of native people have been fundamental to American culture, commerce, and government.”

Dichotomy exists between how this country uses Native American culture and our discourse on Native Americans. It is increasingly acknowledged that the United States government and institutions took steps to eradicate indigenous people. So why do we idolize imagery and names associated with Native Americans? We are surrounded by Native American influences and examples of the appropriation of Native cultures, yet, according to a 2015 study, Manifesting Destiny: Re/Presentations of Indigenous Peoples in K–12 U.S. History Standards, nearly 90 percent of curriculums in the United States do not refer to the existence of Native Americans after 1900.

I understand intimately the erasure of indigenous people from society’s view. Read below to learn about my experience at the museum.

Native Americans: Everywhere & Nowhere

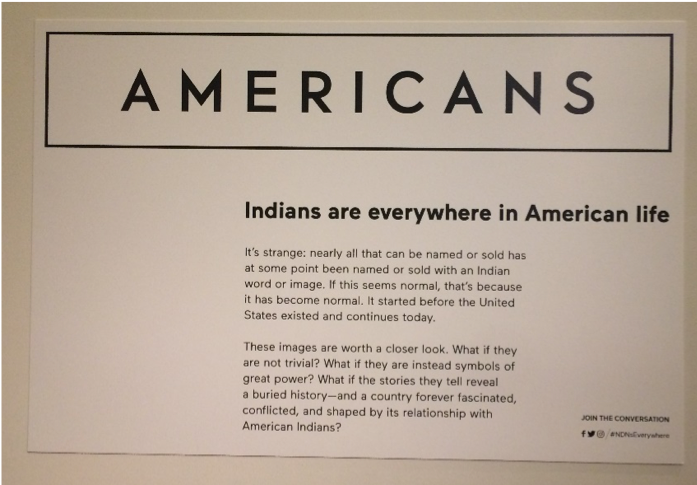

The sign below welcomes visitors as they enter the exhibit. I was immediately struck by the economic perspective invoked in the first sentence: “nearly all that can be named or sold has at some point been named or sold with an Indian word or image.” Commerce lies at the center of the United States’ national identity, and thus does the Indian. If you doubt the truth of this statement, uncertainty vanishes when you walk into the main gallery.

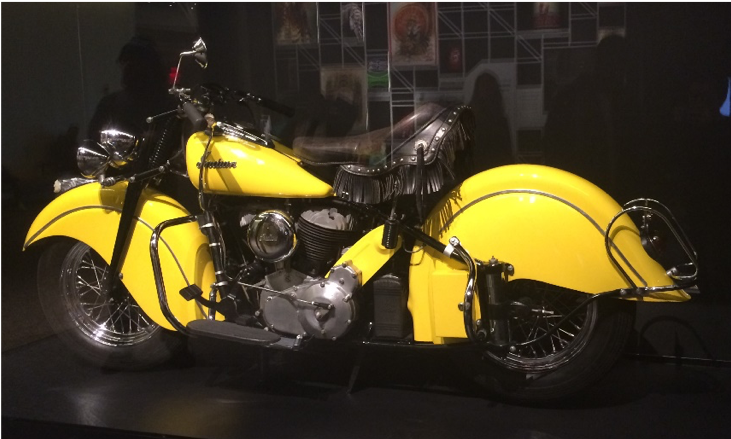

Hundreds of meticulously numbered images and items covered the walls of the oblong gallery. In the middle of the gallery, two touch tables allowed visitors to learn more about an item using its number. Cigarettes, motorcycles, sports teams and merchandise, motor oil, magazine covers, cornmeal, city insignias, whiskey, soda, butter, candy, movies, toys, military fighter jets and torpedoes… a motorcycle?

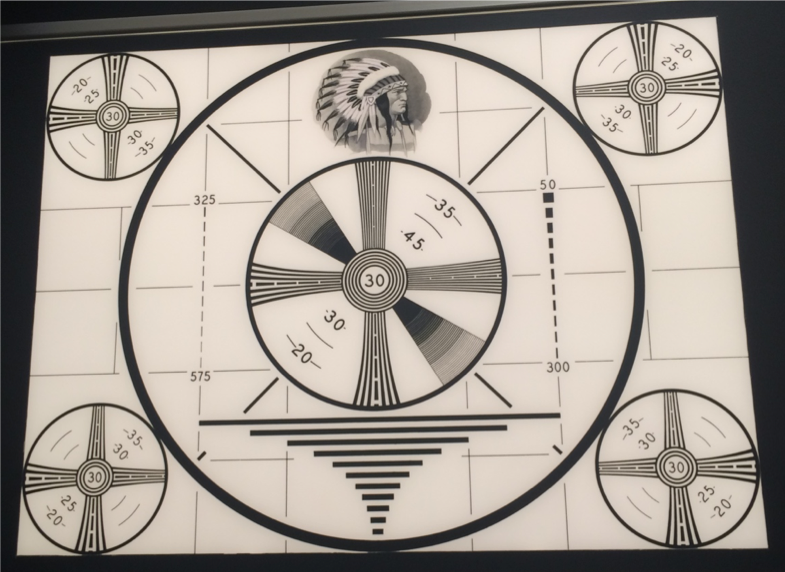

I spent over an hour walking back and forth from different images to the touch tables, reading more about the Tootise Pop wrapper, American Spirits’ packaging, a giant Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon, and the RCA Indian-Head Television Test pattern from 1939, just to name a few.

More than half of the other people milling about the exhibit were white, about evenly split between older people and young families. It being a Sunday afternoon, this made sense, I suppose. While the gallery was filled with the sounds of chatter and movement, this melody melted in the side rooms.

Five side rooms extend off the gallery, three on the left and two on the right. The first two rooms on either side contained “stories”: The Invention of Thanksgiving, Queen of America, The Removal Act, and The Indians Win. Each one briefly examines the history of how and why Native American images and names are so prolific.

Walking through each room, the spaces were very quiet, and the mood reverent. I took care to read all the information and noticed that everyone around me was doing the same.

In the Indian Removal Act room I was greeted with the words, “Even today the Indian Removal Act remains one of the boldest and most breathtaking laws in American history.” Which is a bit disappointing, when you think more deeply about the choice of wording. Boldest and breathtaking? Why not call it what it was: atrocious, unhuman, devastating.

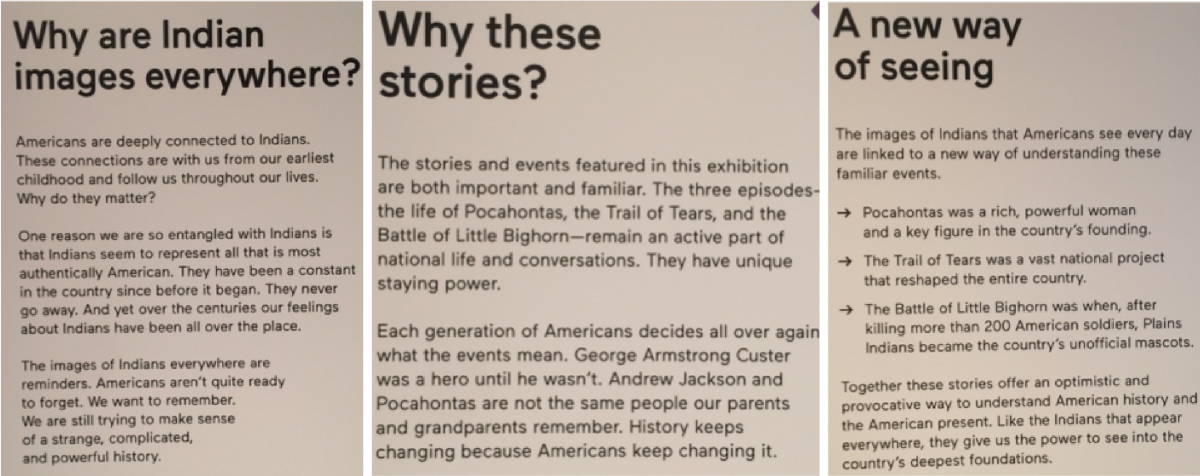

After making my way through the “story rooms,” I entered the final, fifth room. The sign outside read “Americans Explained.” In stark contrast to the first four rooms, this space contained very little color or imagery. The entire room was white and brightly lit. On the wall to the left of the entrance were four large blocks containing text, the last of which I placed at the start of this blog, cut into two pieces.

Videos of individuals, diverse in age and background, played on the wall opposite of the text blocks. Each short film featured one person talking into the camera, describing their reaction to the exhibit, what they learned and felt along the way, what Native American imagery and narrative meant to them.

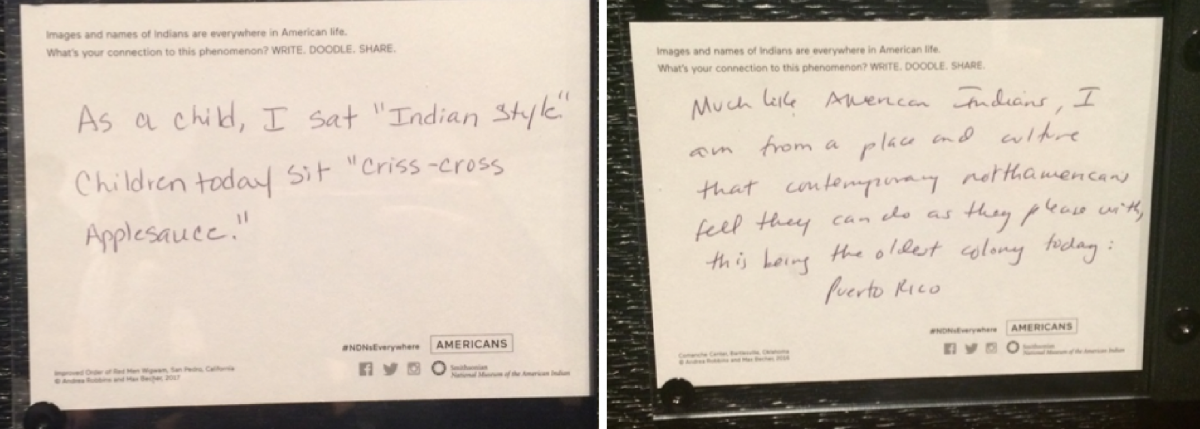

Dozens of postcards filled the wall space to the right of the film strip. These were messages left from previous visitors. Blank postcards sat in the center of the room, and persons were invited to write their own notes and deposit them into bins for a chance to be displayed.

Prior to exploring the fifth room, I was a bit underwhelmed by the exhibit. While the hundreds of images in the main gallery elicited provocative feelings, and the stories in the side rooms offered a nuanced perspective, the overall effect left me wondering about the curator’s overall goal. However, upon entering the fifth room, I finally understood. Everything encountered thus far, all the images, the first four “story rooms,” and the entire layout of the exhibit, suddenly made sense.

Representations of Native Americans from the nonindigenous point of view are stuck in a Machiavellian time-warp. Native Americans images and names are in our pantry, on our televisions, our bodies, our street corners, our money, in our mouths. It’s awe-inspiring, really. And overwhelming.

For where are they, the Native Americans? How is it that they appear everywhere, and exist nowhere?

“Americans” does not attempt to answer that question. Rather, it attempts to get you questioning.

All in all, my first visit to the exhibit reinforced what I already knew, as well as taught me much more. This last room, “Americans Explained,” hastily visited in the final minutes before the museum closed for the day, was by far my favorite part. Reading others’ responses on the cards and hearing their thoughts through the videos allowed me to better understand the exhibit’s purpose and approach.

A Time to Discuss

Following my first exploration, I read several reviews and news articles about the exhibit, all of which are cited at the bottom of this blog. The new information lead me to visit the museum once more in the month of February. My curiosity immediately paid off; previously unnoticed, a clear bin mounted to the wall immediately to my right enticed me closer.

The bin contained about nine large, spiral books: a “Gallery Discussion Guide.” How had I missed this vital piece to the puzzle?

I flipped through the pages of the book and found it to be utterly remarkable.

The book began with an exploration of the gallery area. The first pages asked visitors to look around the room and identify familiar objects, as well as objects connected to the government, such as city seals and military aircraft.

The remainder of the book accompanied the stories featured in each of the four side rooms. Individuals are encouraged to make their way through each room, noticing symbolism and learning about the history and origin of how these stories came to be told, rather than another version.

Additionally, readers are challenged with thinking critically about the implications of these stories, both for the founding of the United States and the lives of Native Americans.

Americans Online

An interactive website allows visitors to explore some of the images and objects on display at the museum. Users click and drag the webpage to search through, selecting artifacts or “stories” individually to learn more.

Unfortunately, you’re unable to search for an item on the website using the ID numbers in the museum. Perhaps this feature could be added, so visitors could go back to items that were of particular interest, even after they’ve left the exhibit.

The stories from the exhibit – The Invention of Thanksgiving, Queen of America, The Removal Act, and The Indians Win – are also on the website in a modified version. I encourage you to use the links above to explore the stories, especially if you’re unable to visit the exhibit in D.C.

Below you will find several links to reviews and news articles about “Americans,” so that you may learn more about the curators’ intent.

For your consideration

As you read this blog, here are some questions for you to consider:

- Native Americans comprise less than one percent of the U.S. population, yet Native American imagery and names seem to be everywhere in our culture. Why do you think this is the case? How is that Native Americans can be so present and so absent in American life?

- The history of the United States is checkered with the mistreatment of Native Americans. Through legislation and policy, the U.S. government once made efforts to destroy native cultures and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society. So why, especially in the past 100 years, do you think Native American imagery has been seen as a marketing tool?

- The names of half the states in the U.S. are derived from Native American terms. In your own community or region, are there towns, streets or geographic features with Native American names? What do you know about the people or cultures behind these names?

- In what ways is the use of Native American imagery and names problematic? In what instances might it be considered “appropriate” or respectful?

- In what ways do imagery, language or cultural traditions associated with other minority groups appear in mainstream U.S. culture? In what ways might the assimilation of these cultural artifacts be okay, and in what instances might it become exploitative or offensive?

- Why do you think that certain stories are told and others not? In one section of the Americans exhibit entitled, “Queen of America,” which is about Pocahontas (you can learn more here), a frieze is presented, which depicts the story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith. In this frieze, Pocahontas is “defying her father and saving Captain John Smith.” It is acknowledged, however, that it is an incident that historians doubt happened at all. Why do you think this particular story was told?

- Do you know of any Native American “hidden history” figures?

Resources

These resources, and much more, can be found in the Moving Forward Initiative resource library.

Dingfelder, Sadie. “Why there’s Redskins merch at the National Museum of the American Indian.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 25 Jan. 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/express/wp/2018/01/25/why-theres-redskins-merch-at-the-national-museum-of-the-american-indian/?utm_term=.7d332b03f152.

Fonseca, Felicia. “New exhibit examines Native American imagery in U.S. culture.” The Columbian, Associated Press, 25 Feb. 2018, www.columbian.com/news/2018/feb/25/new-exhibit-examines-native-american-imagery-in-u-s-culture/.

Kennicott, Philip. “Review | The American Indian museum comes of age by tackling this country’s lies.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 19 Jan. 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/the-american-indian-museum-comes-of-age-by-tackling-this-countrys-lies/2018/01/18/441a4f74-fb9e-11e7-a46b-a3614530bd87_story.html?utm_term=.2750458f181a.

“Looking at Indians, white Americans see themselves.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, 10 Feb. 2018, www.economist.com/news/united-states/21736555-thinking-about-natives-era-nativism-looking-indians-white-americans-see.

Loria, Michael. “Americans at the National Museum of the American Indian.” On Tap Magazine, 27 Feb. 2018, https://ontaponline.com/2018/02/02/americans-at-the-national-museum-of-the-american-indian/

Miranda, Carolina A. “Its not just Chief Wahoo. Why American Indian images became potent, cartoonish advertising symbols.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 29 Jan. 2018, www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-americans-nmai-indians-in-pop-culture-20180122-htmlstory.html.

Rothstein, Edward. “‘Americans’ Review: Detailed Portrait of a People.” Wall Street Journal. Wall Street Journal, 17 Jan 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/americans-review-detailed-portrait-of-a-people-1516229238

Schjeldahl, Peter. “America as Indian Country.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 22 Jan. 2018, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/29/america-as-indian-country.

Shear, Sarah B., et al. “Manifesting Destiny: Re/Presentations of Indigenous Peoples in K–12 U.S. History Standards.” Theory & Research in Social Education, vol. 43, no. 1, Feb. 2015, pp. 68–101., doi:10.1080/00933104.2014.999849.

Smith, David. “Trump doesnt understand history: Native Americans tell their story in DC.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 11 Feb. 2018, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/feb/11/native-americans-indians-smithsonian-trump.