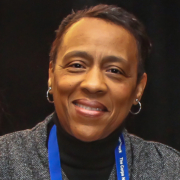

Dr. Andrew W. Kahrl is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Virginia. His research focuses on the social, economic, and environmental history of land use, real estate development, and racial inequality in the 20th century United States.

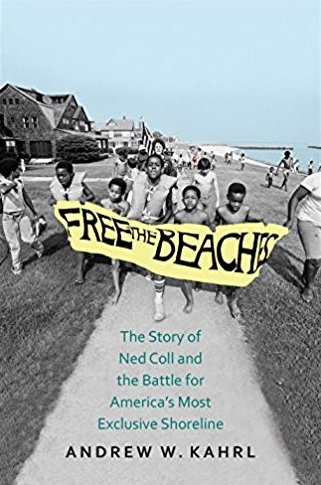

Dr. Kahrl is the author of The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South (UNC Press: 2016), as well as the forthcoming book, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline (Yale University Press: 2018).

As part of The Corps Network’s Moving Forward Initiative, we spoke with Dr. Kahrl about the outdoor leisure and recreation opportunities available to African Americans during the era of Jim Crow. Read our conversation to learn how policies, events and social practices shaped the way African Americans recreated and utilized outdoor spaces in the first half of the 20th century. We also discuss historical influences on the modern conservation and outdoor recreation movements.

Click for Moving Forward Initiative homepage

Tell us a bit about your area of study and how you came to focus on the intersection of race, the environment and the economy in 20th century America?

I wrote a dissertation, that then formed the basis for my first book, that looked at the history of African American outdoor leisure spaces in the Jim Crow South. The question that framed my first book was, “how did African Americans develop parallel social spaces in a segregated society?”

We’re familiar with whites-only swimming pools and parks, but there was less information available about how African Americans created alternative social spaces in a Jim Crow world. What types of spaces – especially outdoor spaces – were available?

I realized early in the research how extensive the network of black social spaces was. The importance of these spaces didn’t just reach into the world of recreation and leisure, but also into black economic life. Two of the main things I uncovered were, 1) just how widespread African American landholdings were in coastal areas, which was something I initially wasn’t expecting. And 2) how critical African American leisure spaces were to local black economies.

In my mind, these findings spoke to how we should look at people’s interactions with the outdoor world not just through the lens of environment, but also through the lens of economy. Furthermore, we should think of Jim Crow not only as a racial regime, but a land regime. Jim Crow profoundly influenced the built and natural environments of the South, both in the way whites excluded people, and in the way African Americans carved out spaces of their own.

For my first book, I gravitated specifically towards the history of black beaches because, for one, there were so many of them scattered throughout the South. These beaches were a product of opportunity: African Americans having land that they owned and could then turn into enterprises.

Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University – via Grist.org

Can you discuss why, in the first half of the 20th century, there was a need and desire to create black-owned leisure spaces?

In the era of Jim Crow, the types of activities from which African Americans were fully excluded tended to involve more intimate spaces: funeral homes, barber shops, restaurants, and leisure spaces, too. These were spaces where segregation was so complete that African Americans’ opportunities to carve out parallel institutions was greatest.

When we think about what people want when they seek out leisure, they want relaxation, comradery. Unless you are seeking to engage in a form of protest or challenge the social order, the last place you as an African American would want to spend leisure time is surrounded by hostile, racist white folks. It stands to reason that African Americans who had the time and resources to carve out moments of leisure would want to find welcoming environments.

It’s important to note how, especially for many working class African American families, it was rare to find moments of respite, and rare to find moments when you could rest from having to deal with white people. Daily interactions with white people in the Jim Crow South could be frustrating, hostile, humiliating – everything that leisure is not. So that gives you a sense of why it was so critically important for African Americans to have spaces of their own.

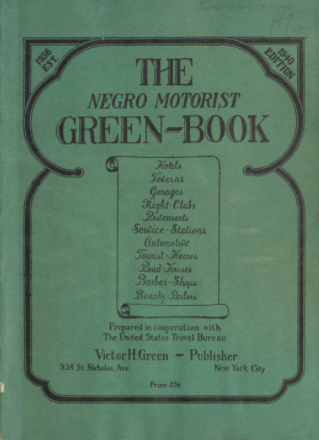

Can you talk about what the Green Book was? What was its purpose and what information did it offer?

Can you talk about what the Green Book was? What was its purpose and what information did it offer?

The Negro Motorist Green Book was a guide – published from 1936 to 1967 – that provided a list of welcoming restaurants, hotels, and other accommodations for African American travelers trying to navigate a Jim Crow world. It was geared towards providing information on a town-by-town, state-by-state basis. If a certain town was not listed, that was a signal to keep driving.

The Green Book primarily provided names of small, black-owned businesses, but, as you get into the last days of its publication – you begin to see corporate chains making it known to readers – who were mostly middle class African Americans – that their business was welcome.

The Green Book existed because America was a racist country. It responded to a need among African American consumers for information about places they could go where their money would be accepted and they would be treated with dignity.

An important point for many African American mothers and fathers with small children was a desire to shield their families from racism. Not to try to create a fantasy world where racism didn’t exist, but to try and prevent any humiliating or dangerous encounters if possible. This need was part of what the Green Book aimed to serve. By patronizing businesses in the Green Book, families would not need to experience rejection.

In doing interviews for my book, one thing noted by African Americans who grew up during this time was that, if their family was travelling a long distance or going through the Deep South, they would leave in the dead of night so they could get to their destination while the kids were asleep. This was to avoid situations where the kids might say, “let’s stop here,” or “I have to use the restroom,” and the parents would need to have a difficult conversation where they’d explain why they couldn’t stop.

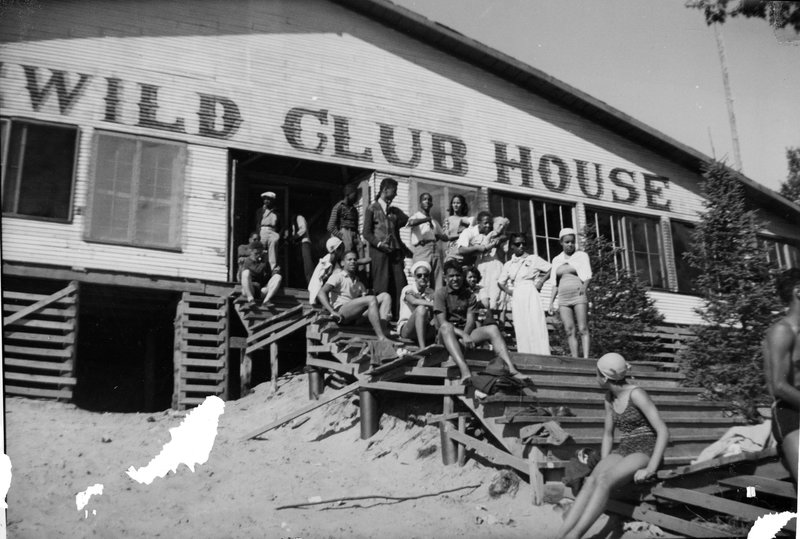

The Idlewild Club House, Idlewild, Mich., September 1938. (Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images) – via NPR.org

Where were black-owned outdoor leisure spaces? Were they predominantly in the South, where racism and segregation would have been more overt?

A lot of African American leisure spaces grew up informally. Many of the black beaches I write about began with black families who owned land who would let it out to picnic groups, church groups, and people seeking a place to relax on the weekend. If you flip through the pages of the Green Book, you’ll find that many of the locations listed as lodging are people’s homes – or what are called “Do-Drop-Ins.” These are places where a black family that owned a house would let out an extra room. It was sort of like an early version of Airbnb.

As you might expect, black-owned leisure spaces grew up around areas with large concentrations of African Americans. They followed the demographic changes that unfolded during the 20th century. In the nineteen-teens and twenties, as the black population grew in northern cities, you began to see black vacation communities sprout up in places like rural Michigan or northern Indiana. In Michigan, there was Idlewild, which was a famous vacation destination for black doctors and professionals who lived in Chicago.

In the South, there were both formal resort communities, as well as destinations that would more resemble a space for local folks or the working class.

Black outdoor leisure spaces were as varied and diverse as black America itself. There were places for the highly educated or, as they were sometimes called, the “aristocrats of color.” These were places like Highland Beach, which is outside Washington, DC on Maryland’s western shore. This was where Howard University professors and the black cultural elite of Washington would go. This was a place where working black families would not feel welcome. The families that lived at Highland Beach worked just as hard as white elite resort communities in excluding certain people from their spaces. On the other hand, you had places that very much catered to working families. Class segregation or separatism was very pronounced in black America, especially when it came to leisure spaces.

Archival photo from Shenandoah National Park – National Park Service historic photos

Would African Americans have frequented national parks? In our research, we came across an archival photo from Shenandoah National Park of a sign pointing towards the “negro area” for camping and picnicking.

I’m not an expert on this, but, from what I’ve read, African American presence at national parks was very, very small. Especially in the South, there was certainly a climate of hostility towards African Americans seeking out these types of spaces. State parks in the South were segregated across the board. There was a great book about this – Landscapes of Exclusion, by William O’Brien – that tells the story of a whole parallel world of black state parks that developed throughout the South. Some of these parks were areas of existing state parks, while some were separate places altogether.

Could you tell us a bit more about African American beaches in the Jim Crow South and what became of these spaces?

The story I tell in my book is one in which many of these places – and, consequently, one way in which many African Americans interacted with the natural world – declined quite dramatically from the 1960s to the present as waterfront properties in the South became highly coveted. African Americans who owned this land often found themselves being swindled out of it or forced off the land by the courts or public officials.

The story of black land ownership in the South in the 20th century is one of decline. The high watermark for black land ownership in 20th century America was 1910. It’s a time we conventionally associate with African Americans lacking political rights and opportunities in the workplace, but part of the story is that, because there were so few avenues of opportunity, black Southerners worked extraordinarily hard to acquire land. Land ownership was a means of liberation. However, this freedom increasingly eroded over the course of the 20th century, even as African Americans gained political rights.

At the time when many African Americans acquired these coastal lands, they were not valuable. In fact, they were probably some of the least desirable properties in the South. Coastal properties were remote, hard to get to, and were often not conducive to largescale agriculture. Additionally, they were, and still are, subjected to violent storms. These were places that, by and large, white Southerners avoided.

As an example, the South Carolina Sea Islands became home to the largest concentration of African American landowners anywhere in the South. This was land that was essentially abandoned by slave owners during the Civil War. Edisto Island was the birthplace of “40 acres and a mule”: the idea of taking land that had been captured or abandoned during the Civil War and redistributing it to the slaves who had worked on it.

In short, these coastal properties were cheap and readily available. Also, if you’re an African American seeking to create as much physical distance between yourself and white society, this was the type of place you would gravitate towards.

Now, of course, things change dramatically over the course of the 20th century as we begin engineering shorelines, building roads and bridges, and taking other steps to make these areas conducive to largescale development. That’s an important story of the 20th century: the story of the increased effort to bring land under control and make it profitable at a time when more and more Americans have the time and means to vacation and buy second homes. That’s the story of how these places became so highly coveted and how African Americans who owned land often found themselves in the crosshairs of speculators and developers.

Most of the black-owned outdoor leisure spaces you write about have died out. Can you talk about why this happened? What would you consider to be the legacy of these spaces?

One of the most obvious examples of the legacy of black beaches and resorts was that these spaces nurtured a whole generation of black performers who would later go on to become some of the most famous artists of the 20th century. James Brown, Otis Redding, Jackie Wilson, Moms Mabley – these were African American performers who would cross over into the mainstream and become world famous, but many of them got their start performing at black leisure spaces.

The important lesson of these spaces is one that I stress in the subtitle of my book: “how black beaches became white wealth in the coastal South.” With the Civil Rights movement and the end of segregation, there is a demise of black Main Streets and other African American cultural institutions and businesses that segregation had necessitated. When this happened, what was the loss to the sense of community and camaraderie these spaces fostered?

Highland Beach Picnic Group, 1930. Image Courtesy of Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Smithsonian Institution – via BlackPast.org

One thing that was undeniably lost was wealth. The places I write about – like the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands, Maryland’s western shore, the Gulf Coast of Mississippi – these are places where the land that African Americans owned in the first half of the 20th century is now some of the most valuable property in the United States.

Property that’s worth in the tens of millions of dollars used to be owned by African Americans and it was taken from them, often through various forms of chicanery and deceit, if not outright theft. The black families that owned that land never saw a dime.

When we have these conversations about the origins and persistence of the racial wealth gap in America, many times people seek to identify all the opportunities that African Americans have been denied. And that’s important, but we often lose sight of what was taken from previous generations. This was wealth that was in their hands, but they were never able to fully realize it. Instead, it became someone else’s wealth. It became the wealth of corporate developers who acquired the land for very cheap. African American families are now sometimes cleaning the bathrooms and tending to the lawns of land that their ancestors owned. That should give us pause when thinking about the legacy of these spaces.

As part of the Moving Forward Initiative, we hope to examine why there is a persistent lack of diversity in visitation at parks and participation in outdoor recreation. Do you see any historical context for this disparity?

Well certainly there’s the role of urbanization and the concentration of non-white populations in inner cities. During the 20th century, you saw African Americans being systematically excluded from becoming homeowners in the suburbs, coupled with the lack of public transportation options to access areas outside the urban core. This severely limited the ability of African Americans living in the urban North to have access to outdoor space.

Additionally, the natural environment has a whole different meaning in the collective memory for African Americans than it does for white Americans. Historically, spaces that for many white Americans provided a sense of adventure were, for some African Americans, a place of fear and uncertainty. These were places where their ancestors or own family members were terrorized. Outdoor areas in the rural South are littered with stories of lynching, violent deaths, unsolved murders – all sorts of crimes were committed against African Americans in these places.

Then, you combine that with the fact that many outdoor destinations that were once familiar to African Americans disappeared with integration. For some African American families, part of why they may have little direct experience with outdoor recreation is because the places that were once a part of their family tradition are gone.

Relatedly, do you see any historical context for the lack of diversity in the mainstream conservation movement?

The conservation movement has, throughout much of the 20th century, been white-dominated and defined by issues that concern white Americans. At the very least, the movement has certainly been oblivious to the concerns of black Americans.

There has been a sense among African Americans that the conservation movement was not for them, it was not in their name. There’s a perception that the interests of the conservation movement are directly in opposition to the interests of African Americans; this is due, in part, to the way opponents of conservation have tried to exploit division

To give you an example, there was a famous controversy in the area around Hilton Head over the efforts of BASF – an international conglomerate – to locate a plant along a waterway. The plant would’ve brought lots of jobs, but also would’ve polluted rivers and streams. Folks in the environmental movement, who were dead-set against this plant being located there, were framed as an enemy for blocking job creation. Part of this was BASF trying to work-up divisions and appeal to African Americans for their support.

That’s just one example of how, particularly in struggling African American communities that need jobs, many have come to see, either through direct experience or perception, that the interests of the conservation movement come at the expense of their own pocketbooks.

You have another book coming out soon regarding race and beaches in America. Could you tell us a bit more about the issues this book explores?

You have another book coming out soon regarding race and beaches in America. Could you tell us a bit more about the issues this book explores?

This is a story of the Northeast, and particularly Connecticut. In a way, I’m looking at the flipside of the story that I write about in my first book in that I’m telling the story of exclusive white beaches along Connecticut’s Gold Coast. These are communities that worked diligently to exclude the public.

Alongside of that, you have the issue of segregation in the North. The children of those who migrated north during the Great Migration are, by the time we get to the 1960s and ‘70s, living in very concentrated urban neighborhoods with very little practical access to the great outdoors due to a whole host of factors.

So that’s setting the stage for the story that unfolds, which is one in which a social activist – Ned Coll – started an anti-poverty organization that was dedicated to improving the living conditions within Hartford’s black neighborhoods. He was also trying to engage the support of white America – specifically liberal white America: the folks that expressed their solidarity with African Americans, yet often lived in all-white suburban communities and had very little direct contact with African Americans. Coll was trying to break down those walls separating white and black America.

One idea that he latched onto was to get black children in Hartford and other cities out of the ghetto in the summer and down to the beach. This would provide opportunities for them to venture into new places, and would help foster better understanding among white Americans.

But when he tried to bring a busload of city kids down to the Connecticut coast, he discovered there was nowhere to go. Almost the entire state shoreline was closed off to the public. At that point he became an activist, a very creative and inventive one, for the cause of open beaches.

He would do amphibious landings where they would come ashore and kids would get off the boats and play on the beach. Legally, the beach belonged to the public, but you had to get creative if there was no way you could get to the shore from land.

He was trying to draw attention to this lack of access to the shoreline. Also, he was trying to draw attention to the real deprivation of the urban poor, especially in regard to outdoor spaces and outdoor leisure. He wanted to challenge the liberals that liked to talk a lot about concern for the poor, but did very little in their own lives to improve conditions for marginalized populations.

For Your Consideration

As you read this blog, here are some questions for you to consider:

- Scroll through copies of the Green Book using this digital collection from the New York Public Library. Do you notice any patterns in the advertisements or listings? How does the Green Book change over the years and what might these changes say about society?

- What do “the great outdoors” mean to you? What comes to mind, or what do you feel, when you hear that term? What has shaped your thoughts and feelings about the outdoors?

- In the modern day, have you witnessed any racial or ethnic division in how people choose to (or are able to) recreate and spend leisure time? If so, why do you believe these separations exist? How might these divisions be problematic? In what ways might they not be problematic?

- When you were growing up, or in your own family and friend groups today, where did/do you go to vacation or recreate? To what extent were/are your leisure decisions based off traditions with which you were raised?

- For Corps: When working with Corpsmembers who may have limited experience living and working in the wilderness, what do you do to support them? What are reasons why these Corpsmembers might have limited exposure to camping, hiking, boating or other outdoor activities in which your crew engages? Have you ever had a discussion with Corpsmembers about barriers to outdoor access?

Resources & Supplemental Readings

View the complete Moving Forward Initiative Resource Library here.

Douglas, Leah. “African Americans Have Lost Untold Acres of Land Over the Last Century: An Obscure Legal Loophole is Often to Blame.” The Nation, 26 June 2017. Web, https://www.thenation.com/article/african-americans-have-lost-acres/, 07 November2017.

A look at how African Americans gained land following the Civil War, but gradually lost it throughout the 20th century due to a variety of reasons, including legal loopholes, forced buy-outs, discriminatory lending practices, and the Great Migration.

Engle, Reed. “Segregation/Desegregation,” Resource Management Newsletter, January 1996. Web, https://www.nps.gov/shen/learn/historyculture/segregation.htm, 07 November 2017.

Cultural Resource Specialist Reed Engle looks at the segregation and desegregation of Shenandoah National Park.

Goffe, Leslie. “How the 1964 Civil Rights Act Cost Black America,” New African Magazine, 08 May 2014. Web, https://newafricanmagazine.com/how-the-1964-civil-rights-act-cost-black-america/, 07 November 2017.

A look at how the Civil Rights Act led to the movement of African Americans to white suburbs and the decline of African American businesses, cultural institutions and community in urban areas.

“The Green Book.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book#/?tab=about. 12 September 2017.

Digital copies of the several editions of The Negro Motorist Green Book, a travel guide published annually from 1936 – 1967 that listed lodging, restaurants and businesses that catered to African Americans.

“Idlewild, Michigan (1912 – ).” BlackPast.org, https://www.blackpast.org/aah/idlewild-michigan-1912. Accessed 07 November 2017.

Kahrl, Andrew W. The Land was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South. Oxford University Press. 2012.

By reconstructing African American life along the coast, Kahrl demonstrates just how important these properties were for African American communities and leisure, as well as for economic empowerment, especially during the era of Jim Crow in the South.

https://www.amazon.com/Land-Was-Ours-Beaches-Coastal/dp/1469628724

Leland, John. “Investors Move Next Door, Unsettling a Black Beachside Enclave,” The New York Times, 25 August 2016. Web, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/26/nyregion/new-neighbors-unsettle-black-enclave-sag-harbor-hills.html?_r=0, 07 November 2017.

Some residents of Sag Harbor, NY have grown wary of an increasing number of investors sweeping up properties in the area.

O’Brien, William E. Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South. University of Massachusetts Press. December 2015.

From early in the twentieth century, the state park movement sought to expand public access to scenic American places. During the 1930s those efforts accelerated as the National Park Service used New Deal funding and labor to construct parks nationwide. However, under severe Jim Crow restrictions in the South, African Americans were routinely and officially denied entrance to these sites. In response, advocacy groups pressured the National Park Service to provide some facilities for African Americans. William E. O’Brien shows that these parks were typically substandard in relation to “white only” areas.

https://www.umass.edu/umpress/title/landscapes-exclusion

Winerip, Michael. “A Legend and his Catskills Resort for Blacks,” The New York Times, 15 July 1985. Web, https://www.nytimes.com/1985/07/15/nyregion/a-legend-and-his-catskills-resort-for-blacks.html?pagewanted=all, 07 November 2017.

A look at Peg Leg Bates Country Club, a resort for African Americans in the Catskill Mountains of New York that operated from the 1950s to the 1980s. The business closed two years after publication of this article and now sits abandoned.