By Marie Walker

A Moment of Voice with Marie Walker, COO of The Corps Network

Each of us views the world through the lens of our life experiences. Different people can watch the same event unfold, but have different responses. I recently witnessed an event that probably seemed mundane to the average person; I, however, was overwhelmed.

In my capacity as COO of The Corps Network, I’ve had the opportunity to periodically travel to the Gulf Coast. Our organization is proud to help lead GulfCorps, an initiative to train hundreds of local young adults, from Texas to Florida, for jobs in coastal restoration. On a visit this past spring, I stayed at the same hotel where I usually stay, close to The Corps Network’s office in Gulfport, MS. Between meetings and travel, I had time to explore. I’m glad my colleague Stephanie suggested I go to the beach.

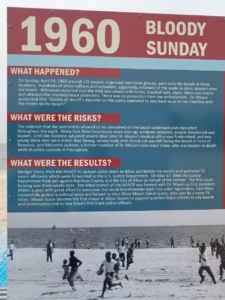

I had visited Biloxi Beach dozens of times before; it’s just steps from the hotel. This visit, however, was different. The community had recently installed informational signs about “Bloody Sunday,” an event that happened on the beach nearly 60 years ago.

Biloxi Beach was once segregated. Black people were confined to visiting a small portion of the 26-mile coastline. To protest this injustice, a local physician named Dr. Gilbert Mason organized what is considered the first act of civil disobedience in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era.

Biloxi Beach was once segregated. Black people were confined to visiting a small portion of the 26-mile coastline. To protest this injustice, a local physician named Dr. Gilbert Mason organized what is considered the first act of civil disobedience in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era.

On Sunday, April 24, 1960, Dr. Mason led more than 100 black men, women and children in a “wade-in.” Demonstrators arrived at the beach wearing their swimsuits, ready to assert their rights and peacefully enjoy the beachfront they’d been denied. They were met by a white mob. The police stood by while white people threw stones, threw punches, and even fired shots at black demonstrators. Despite the violence, further wade-ins took place and the NAACP got involved. Finally, in the late ‘60s, the beach was open to all.

I had never heard of the Biloxi “Bloody Sunday.” I read the informational signs on the beach with a mix of feelings: interest, sadness, anger, respect for those who had stood up for what is right. Near one sign, I overheard a man chatting with a couple: he had been at the beach on that day in 1960 and witnessed the demonstration devolve into violence. Feeling grateful to that man for willingly sharing his firsthand experience, I made my way to a bench to think. My quiet moment of reflection did not last long.

Right in front of me, I saw a young black family make their way to the beach; a man and a woman led by three small children, who happily – and freely – charged towards the water. I felt a rush of emotion as I watched the little boy, giggling and smiling, run back and forth between the waves and his family. He didn’t have a care in the world.

I was struck with the memory of an incident that happened to me when I was his age. My grandfather took me to a park in West Virginia. We were sitting in the picnic area when I caught sight of the “Ridge Runner,” a small train ride for kids…but not for all kids. I asked my grandfather if I could please ride the train, but he told me no, “that’s not for colored children.” I was probably disappointed, but I don’t remember putting up a fight. That was the way things were. I grew up with segregated water fountains and bathrooms; I remember riding on the “colored section” of the passenger train with my grandmother. Being told “no” was nothing new.

When I saw those children playing on the beach, I thought to myself, they will never know why it is they can get up on a Saturday morning, bring their pails and shovels, and play in the sand. They will never experience the kinds of restrictions children of my generation faced. Most people around me probably paid no mind to the family playing in the waves, but I was struck.

Yes – our country has a long way to go on the road to racial equity, but, in that moment, I was overwhelmed by how far we’ve come. I thought, “this is why we do what we do.” Change happens when average people stand up for their beliefs. I am proud of my colleagues and our member organizations that are actively promoting diversity, equity and inclusion in the Corps movement.

I am glad I went to the beach that day. Seeing that exhibit on the wade-ins and seeing those children play was a reminder of how things were and how things have evolved. It’s important to have these kinds of reminders: we need to learn from the past and show our respect to the brave change-makers who came before us. Part of me, however, wants us to all be like that little boy: to be able to enjoy a day at the beach without a second thought and without the burden of history.

This blog is part of The Corps Network’s Moving Forward Initiative blog series.

Related Material:

- The National Science Foundation recently announced plans to name a $100 million oceanographic research ship after Dr. Gilbert Mason, the civil rights leader who led the Biloxi Wade-Ins.

- Watch this video from the National Museum of African American History and Culture, #APeoplesJourney: From Sit-Ins to Wade-Ins