Blog by Cassandra Ceballos, Programs Assistant, The Corps Network

The Corps Network’s Moving Forward Initiative – supported by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation – seeks to address bias and structural racism in the conservation workforce and help increase the employment of young adults of color in public lands management and conservation-related careers.

As part of this initiative, we aim to provide information to help people develop a foundation to understand the history, policies, practices and societal dynamics that have shaped our country and the conservation field. This blog will explore the relationships between Native Americans and the first permanent British settlements in the present-day United States. This week, as we celebrate Thanksgiving – a holiday built around the lore of peaceful and mutually-beneficial relationships between Native Americans and Pilgrims – we feel it’s important to add our voice to the growing conversation about the inaccuracies of these stories.

The British – who would later become the first “American citizens” – viewed the indigenous people as subordinate and uncivilized due to their nomadic lifestyles and “underutilization” of the land. The settlers’ hunger for expansion drove them to pursue goals of eradication. They took actions which displaced native peoples and redefined tribes’ relationships with ancestral lands. Over a period of 300 years, from 1609 to 1900, Native American tribes went from inhabiting the entire land area, to living on specifically defined “native reservations.” Long before the founding of the United States, countless acres were taken through illegal treaties, trickery, and bloodshed.

These preliminary encounters between Native Americans and colonists laid the foundation for a tradition of land grabbing that repeated itself through the Revolutionary War of 1776, and later through policies of the United States federal government. The phenomenon of taking land from the Native Americans under the banner of supremacy is highly relevant to the Moving Forward Initiative. European settlement of North America altered the way people had interacted with the land for millennia, and proved devastating for indigenous communities and their people.

The structural dynamics responsible for the erosion of indigenous land sovereignty continues to the present. Today, exposure to environmental degradation is a concern for Native Americans residing on reservations. However, barriers, including explicit and implicit biases, have historically prevented native voices from participating fully in conservation and preservation discussions. Meanwhile, their historical and sacred sites are celebrated as treasures of America’s “public lands.”

Native Americans arrived in the Americas about 15,000 years ago. It’s difficult to quantify the population of indigenous people inhabiting North America prior to European arrival in the late 15th century; estimates range from 4 million to over 100 million. What is certain, however, is that their numbers greatly dwindled following contact with white settlers.

The greatest threat to Native life came from diseases, such as measles and small pox, unknowingly carried by Europeans. These diseases spread farther and faster than Europeans themselves. Despite this fact, it’s important to examine the direct impact of European imperialism and colonization on the indigenous people of the present day United States. In the Americas, modern society was built on land-grabbing.

European Contact Pre-1600s: Glory, God and Gold

European empires began exploring the New World over 500 years ago, laying claim to land and riches for their respective crowns. Dutch and French settlers established mutually-beneficial trading relationships with indigenous people in present-day Canada and the Ohio River Valley. In contrast, the Spanish initially treated the native peoples of South and Central America as enemies to be eradicated in order to take control of the region’s natural bounty of gold. However, the Spanish turned toward a policy of assimilation through Christianity in the early 1500s. By the mid-16th century, Spanish priests were successfully “missionizing” the native people in established communities. Much intermingling took place between the two groups through marriage and reproduction, creating a majority population of mestizos.

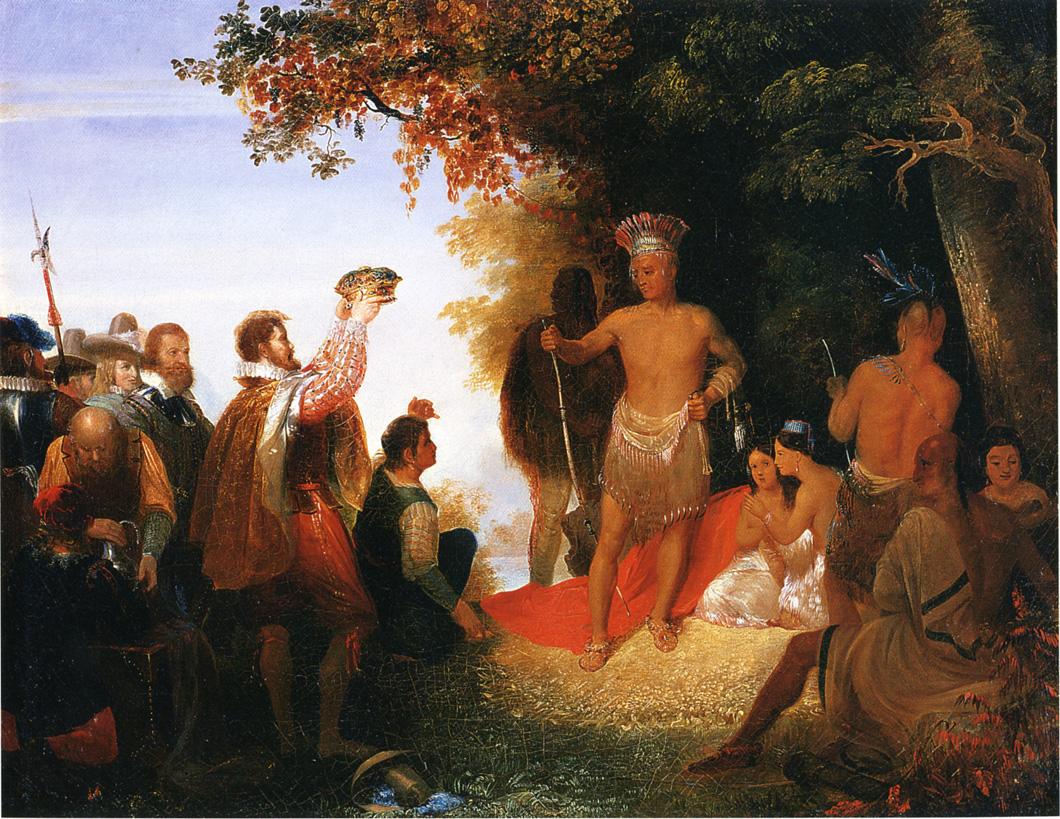

The Coronation of Powhatan – John Cadsby Chapman (1835)

The Settlement of Jamestown

While the British were nearly a century behind other European countries in colonizing North America, they did not follow their counterparts’ policy of missionizing. Britain created its first permanent settlement at Jamestown in 1609, primarily as a temporary venture to amass wealth. Most of the early colonists came from upper-class English families and arrived heavily backed by private investors. In contrast, Pilgrims formed the colony at Plymouth in 1620 not for riches, but to escape religious persecution in England. Although differing in motivation and social organization, the English settlers at Jamestown and Plymouth both engaged destructively with indigenous peoples

The English at Jamestown and the Algonquian-speaking tribes inhabiting the area, led by Chief Wahunsunacawh, lived in relative peace for the first few years after English settlement. Unfamiliar with the Algonquian language, or simply unwilling to learn, the white settlers used the name “Powhatan” for Wahunsunacawh and called the tribes of his kingdom “Powhatans.” Neither group desired military conflict, as fighting would distract from other goals, mainly wealth accumulation for the English and maintenance of chiefdom for the Powhatans.

Conflict arose at the end of 1609 when the English found themselves without enough food. Attempts to raid the Powhatans’ food stores proved largely unsuccessful; nearly all of the settlers died of starvation in the winter of 1609-1610. With supplies and numbers depleted to almost nothing, and the sobering realization that Virginia would not yield the same mineral riches as discovered by the Spanish in Latin America, the Jamestown settlement abandoned the colony and sailed back to England in 1610. But, while journeying down the James River, the group encountered Lord De La Warr, sent from England with ships of supplies.

The Anglo-Powhatan Wars

The arrival of De La Warr changed the relationship between the English colonists and the native people inhabiting present day Virginia. De La Warr, experienced in warfare from his time spent colonizing Ireland for the British, soon took control of Jamestown and launched aggressive military assaults against Chief Powhatan and the Powhatan people, known as the First Anglo-Powhatan wars. The series of conflicts temporarily ended in 1613 when John Rolfe married Pocahontas, the daughter of Powhatan.

Although peace negotiations appeared temporarily successful, skirmishes continued between the English and native peoples as settlers continued to push westward. Opechancanough, who assumed leadership of the Powhatans following the first Anglo-Powhatan War, orchestrated a major surprise attack on English settlements in the spring of 1622, inciting the Second Anglo-Powhatan War. This maneuver killed nearly one-third of the settlers in Virginia. For the next decade, the English continuously attacked and raided North American settlements, greatly depleting the number of indigenous people living in the area. When a peace agreement was finally reached in 1632, the Powhatans found themselves permanently displaced from the present-day Chesapeake Peninsula.

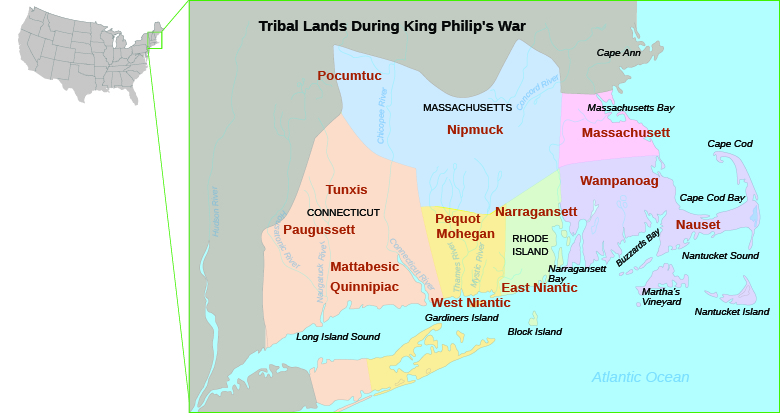

This map indicates the domains of New England’s native inhabitants in 1670, a few years before King Philip’s War. Image credit: “English Settlements in America” by OpenStaxCollege, CC BY 4.0. – Via Khan Academy

The Pilgrims

As Opechancanough prepared to launch his ambush in Virginia, the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts in 1620 and were met by Natives belonging to the Wampanoag Nation, which contained numerous distinct tribes.

At first, certain sects of Wampanoag and the Pilgrims worked together under Chief Massasoit; the tribes needed allies for defending their territory from rival groups, and the Pilgrims desperately needed help learning how to survive in their new environment. Not all Native Americans supported an alliance with the Pilgrims, namely the Massachusetts and Narragansetts, as they saw the settlers’ occupation as a threat to their way of life.

An uneasy peace between Natives and Pilgrims lasted for over forty years until Metacomet succeeded Massasoit as chief of the Wampanoag people in 1662. Metacomet, similar to his Massachusetts and Narragansetts counterparts, viewed the increasing number of settlers as hazardous to Native land.

Cultural differences and misunderstandings played a large role in the conflicts over land. When treaties were signed between the Pilgrims and Natives, the Pilgrims sought to own the land through privately held property rights. Meanwhile, the Natives thought the Pilgrims simply wanted permission to hunt or farm the land, as Native property values centered around communal use by and for the group.

Throughout the 1660s, tensions rose sharply between the two cultures as Native American sovereignty waned due to the loss of land from European encroachment. In 1671, Metacomet, whom the Pilgrims called King Phillip, was ordered to the town of Taunton where the settlers forced him to sign a new peace treaty. History tells us that a humiliated Metacomet returned to his tribe and commenced organizing an inter-tribal resistance against the colonists.

The details of the events taking place in the four years following the incident at Taunton in 1671 remain unclear. However, in the Spring of 1675, all-out warfare commenced between Metacomet’s faction of tribes and the Pilgrims. Known as King Phillip’s War, fighting only lasted fourteen months, but brought unspeakable damage and loss of life. The war ended in August of 1676 when the British beheaded Chief Metacomet.

Of the roughly 4,000 individuals killed over the fourteen-month period, three-quarters were Native Americans. The handful of Natives surviving either fled west, were executed, or sold into slavery. Similar to the outcomes of the Second Anglo-Powhatan war, this defeat of the New England indigenous populations essentially ended their inhabitance of the New England region.

The Lasting Consequences

Between 1700 and 1775, the British population, including their enslaved persons, increased ten-fold, from 250,000 to approximately 2.5 million. An expanding population requires expanded land holdings on which to settle.

The history of warfare, trickery and misunderstandings outlined above are not unique to Jamestown and Plymouth. Beginning with Jamestown, a 350-year pattern of near-constant conflict brought all but a handful of native lands under the jurisdiction of the United States. Over the course of the nineteen and twentieth centuries, a series of legislative actions and legal mandates attempted to distribute, and in many cases, shrink, the land held by indigenous peoples. Of the 2.3 billion acres composing the United States, Native American reservations comprise approximately 56 million acres, or less than 3 percent of total land mass.

For Your Consideration

As you read this blog, here are some questions for you to consider:

- Read this opinion on Native American Heritage Month by a citizen of the Blackfeet Nation. What are your feelings on the observance of cultural and ethnic recognition “holidays?” What is their purpose? How are they useful, and in what ways might they be problematic?

- What do you know about the indigenous people of your state or region? What do you know about their culture, traditions or beliefs?

- Spend some time on this interactive map which chronicles the loss of Native American land from 1784 to the present. You can click on specific tracks of land to learn when and how it was seceded, or designated a reservation. As you familiarize yourself with the map, what stands out to you?

- Research: Were there any Native American settlements in your town or city? What became of these places and people? Where are they today?

- What do you know about the relationship between the U.S. Government and Tribal Governments?

- In American schools, many of us grew up learning “sanitized” versions of historical events and inaccuracies about Native peoples and their cultures. What can be done to correct some of these past teachings and increase awareness? What can schools do today to better educate students?

- For Corps working on Public Lands: How, if in any way, does this narrative conflict with the traditional narrative surrounding public lands? What role can you play in ensuring an honest and holistic conversation about the historical formation of America’s public lands system?