The following is part of the Moving Forward Initiative blog series.

By Allison Puglisi

Ph.D. Candidate, American Studies, Harvard University

This is the second of a two-part blog series on the hopes, concerns, and activism of environmentalists of color. Part one discussed the United Farm Workers’ (UFW) fight against pesticides, as well as other environmental events in the 1960s and 1970s. Part two, below, resumes the story at the end of the 1970s.

At that time, America witnessed several key changes: deregulation of industry, setbacks in workers’ rights, a housing crisis, and the start of a sharp rise in the prison industry. Environmentalists of color were committed to addressing all of the above. They also believed the environmental movement had a responsibility to prioritize the concerns of those most at risk: people of color and low-income people. This belief would evolve to become the environmental justice movement.

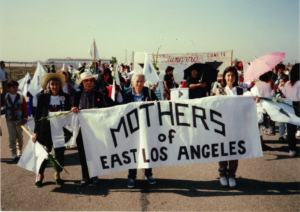

*Banner above is a photo of MELA, Mothers of East Los Angeles.

Northwood Manor

Northwood Manor

In spring of 1978, Browning-Ferris Industries (BFI) sought a permit for their latest project: a landfill in predominantly black northeast Houston. BFI had already acquired a plot of land, and after all the necessary arrangements were made, they would begin to build. They had not paused to consider that the plot was next to a residential community.

That community was Northwood Manor, a mostly black subdivision. As soon as the residents learned a landfill was planned near their homes, they voiced their concerns. As historian Elizabeth D. Blum points out, the landfill’s proposed location was not far from the local high school. Residents were worried about their children’s safety. One parent, Mildred Douglass, was certain that “over a long period of time . . . [the landfill] would cause some type of health problem.” Another parent, Margaret Bean, told Blum there were no “sidewalks out here. I was concerned because the kids were walking home and . . . these big old Browning-Ferris trucks [would be] going up and down the street. I thought some of these kids might get hit by these trucks.”

Bean started knocking on her neighbors’ doors to inform them about the impending landfill. Soon after that, she joined forces with two other women in the neighborhood: Patricia Reaux and Louise Black. The three women became known as the “Gunfighters” because, in Reaux’s words, “they knew that if we were going to fight, we would fight to the end.”

The Gunfighters used a variety of strategies: they called and visited their neighbors, handed out pamphlets, held demonstrations, circulated petitions, and hosted frequent “clean-up days” in their neighborhood. They also hired a lawyer named Linda McKeever Bullard, who prepared to argue that the siting of the landfill was racially discriminatory. The Gunfighters, meanwhile, helped her case by conducting research on Houston’s landfills.

Warren County

The same year that BFI proposed the Texas landfill, a similar issue emerged in Warren County, NC. It began when Robert, Timothy, and Randall Burns drove through the county with 50,000 tons of toxic waste.

The waste came from Ward Transformer Company, an electrical equipment company owned by Robert Ward. To avoid the cost of proper disposal, Ward hired the Burns family to dump the waste illegally along the highway.

The state of North Carolina sued and sentenced Ward and the Burns family, but 50,000 tons of waste containing polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)—a toxin and potential carcinogen—still lay strewn across the county. With approval from the EPA, the state of North Carolina declared its plans to open a landfill in Warren County and move the PCBs there.

The residents of Warren County demanded to know why they should have to live with Ward’s waste. They held demonstrations at the site, and in 1982, they enlisted the NAACP to represent them in court. Like McKeever Bullard, the NAACP argued that North Carolina and the EPA had allowed the landfill in their community specifically because it was black and low income.

Neither the Warren County case nor the Northwood Manor case was successful in court. In both Texas and North Carolina, activists were able to delay but not ultimately prevent the landfills. Still, the movements were successful in pushing many people—for the first time—to consider the relationship between racism and environmental degradation. As Blum writes on Northwood Manor, “The impact of the Bean case lies not in its result . . . Bean yielded a new cause to which [environmentalists of color] energetically applied themselves. Over the next few years, the movement gained in prominence, drawing support from other scholars and activists. During the 1980s, activists in the environmental justice movement developed definitions of their movement in strong opposition to their perceptions of the ‘mainstream’ environmental movement.”

The residents of Northwood Manor and Warren County laid the groundwork for later organizing, and they inspired other groups. One such group was the United Church of Christ (UCC).

The UCC had been following the events in Texas and North Carolina. Its Racial Justice Committee decided to conduct research on environmental hazards in communities of color. In 1987, they published their findings in a report still cited today: Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. The report found that race was the most important factor in the siting of landfills, processing plants, and other hazards. It also determined that three out of every five black and Latinx Americans—and half of Asian and Native Americans—lived in “communities with uncontrolled toxic waste sites.”

With Toxic Wastes and Race, the UCC started an important conversation—a conversation much of America, unfortunately, was unwilling to have. In many ways, the politics of the 1980s ran counter to the UCC’s views and values. The decade was marked by deregulation of industry, large tax cuts, and budget cuts. It was also a challenging decade for environmental issues. Then-President Ronald Reagan hired James G. Watt as Secretary of the Interior and Anne M. Burford to head the EPA. Both were criticized and eventually pushed to resign: Watt, for insensitive remarks toward people of color and people with disabilities, and Burford, for “mismanagement in cleaning up toxic waste.” Reagan, too, was rebuked for his 1981 statement that “trees cause more pollution than cars.”

Local Struggles, Broad Visions

On the local level, grassroots environmentalist groups were responding to these trends. In 1986, a group of mostly Chicana mothers formed the Mothers of East Los Angeles (MELA), which still exists today. The mothers originally came together to challenge a $100 million prison planned in their neighborhood, but later organized against an oil pipeline and waste incinerator as well. At first glance, these three projects seem separate and distinct—but to MELA, prisons, incinerators, pipelines, and chemical plants all fell under the same category: large industrial projects designed to damage both the land and its residents’ quality of life. Since its founding, MELA has pushed environmentalists to rethink what constitutes an environmental issue.

MELA is not the only group to push these boundaries. Also in California, a number of Asian and Asian American groups have made an environmentalist case for workers’ rights. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s—when Silicon Valley was a technology manufacturing hub (and not just an information technology hub, as it is today )—its labor force was comprised mostly of Asian and Latinx women. Very few were unionized, and as Julie Sze points out, this posed serious consequences: “the health and environmental effects of computer production-line labor are numerous, and particularly destructive to reproductive and nervous systems (such as triggering miscarriages).” To address this, groups like the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition (SVTC) emerged to place pressure on the computer industry and educate people on matters of environmental health.

The First Summit

The First Summit

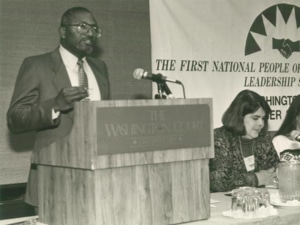

In October 1991, local environmental activists from across the country came together and held the first ever National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. 300 people of different races, from all U.S. states and the Americas, descended on Washington, D.C. to – as Dana Alston put it – “redefin[e] environmental issues in their own terms.” They heard from Havasupai activists fighting uranium mining in Arizona, black activists challenging the petrochemical industry in Louisiana, Western Shoshone activists organizing against nuclear testing in Nevada, and many others. They informed one another about their issues, they shared strategies, and they drafted and ratified “The Principles of Environmental Justice.”

On one hand, the Principles affirmed what many already felt: that people of color were most affected by environmental degradation, and that mainstream environmentalism had not met their needs. At the same time, the document offered a vision of justice that was both forward thinking and cognizant of past violence. It acknowledged how slavery and colonialism shaped – and presently shape – American politics. It also indicted the military industry, declared support for workers’ rights, and “affirm[ed] [indigenous peoples’] sovereignty and self-determination.”

The Principles retain their relevance today, as the residents of Flint, MiI continue to doubt the quality of their water, and the people of Standing Rock Sioux Reservation continue to organize against oil pipelines nationwide. Today’s environmentalists of color are not an anomaly or contradiction. They are part of a long-standing tradition that dates back to the Gunfighters and earlier: a tradition that links environmental rights with human rights.

Reflection Questions:

- Many environmental justice groups were led by women, and had mostly women members. Why do you think this is? How might women’s rights and environmental justice be related?

- Take a look at the Principles of Environmental Justice here, on page 16. The US Constitution reads, “We the people . . .” while the Principles begin, “We the people of color . . .” What do you find interesting or surprising about the Principles?

- People of color today–in Flint, Standing Rock, and many other places–are still fighting for clean and safe resources. What do they have in common with the activists in the twentieth century, and what is different?

Resources

All sources cited in this piece can be found in the Moving Forward Initiative Resource Library.