The Corps Network’s Moving Forward Initiative – supported by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation – seeks to address bias and structural racism in the conservation workforce and help increase the employment of young adults of color in public lands management and conservation-related careers.

As part of this initiative, we aim to provide information to help people develop a foundation to understand the history, policies, practices and societal dynamics that have shaped our country and the conservation field.

Brian McCammack is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Lake Forest College in Illinois. He is the author of, among other works, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago. We spoke to Dr. McCammack about his research into the intersection of environment and race in the Midwest during the “first wave” of the Great Migration.

What was the Great Migration?

The first wave of the Great Migration, which my research focuses on, is dated to roughly between 1915 and 1940; the quarter-century or so between World Wars I and II. This is a time when you have 1.5 million African Americans leaving the South for the urban North and settling in cities like Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, etc.

This movement is driven by racial oppression in the South, the tenant farming system, the rise of Jim Crow, disenfranchisement. There are also the labor demands of WWI in the North, the hope of making a better life, finding better jobs, and having at least more of a semblance of equality.

Chicago in particular, along with New York, are the two epicenters of the Great Migration. Chicago’s African American population grew extraordinarily during this period. Between 1910 and 1940, the African American population more than sextupled. Before the Great Migration, only 44,000 African Americans lived in Chicago; by 1940, on the eve of WWII, you have more than a quarter-of-a-million. This dramatically changes not just the demographics of the city, but the culture. You also begin to see, in really stark ways, the beginning of segregation patterns.

Part of what my research aims to do is push back on this notion that the kinds of environments where African Americans found themselves and were able to visit in the city were exclusively tenement houses and unhealthy environments. That really becomes too much of the story and discounts the ways African Americans found slices of the outdoors, both inside and outside the city.

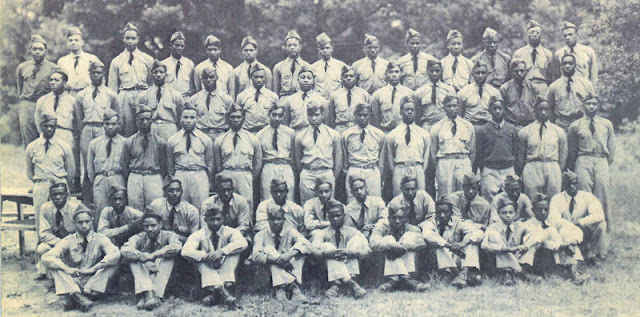

From Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal

Can you talk about African American enrollment in the Civilian Conservation Corps in the Chicago area?

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) is created during the 1930s. An interesting thing about that for me is that during the Great Migration – and I’m painting with very broad strokes – you see African Americans leaving manual labor jobs that are directly connected to the soil, whether you’re talking about tenant farming or extraction industries in the South. They’re leaving a lifestyle of knowing the land through labor. Then, when they move north, African Americans are, by and large, getting jobs in factories. In many cases, migrants are leaving the South expressly to get away from knowing nature through labor, because tenant farming was an exploitative relationship. Industrial jobs in the North are arguably just as exploitative, but they do pay better and there is slightly more of a chance for advancement.

When the CCC forms, tens of thousands of young black men – who either themselves migrated out of the South when they were young children, or whose parents migrated out of the South to escape outdoor manual labor – are now going back to the land.

So that chapter of my book explores what it means for African Americans in the North, in the midst of the Great Migration, to go back to the land and know it through labor rather than through leisure, which, increasingly during the Great Migration, is how many African Americans come to experience and seek out nature. The CCC is an outlier – a callback to a relationship with nature that thousands of African Americans had left behind in the South.

Considering many of these young men or their parents had escaped exploitative labor on the land in the South, how would young African American men have perceived the CCC? Was it seen as a good opportunity?

A big draw was the dollar-a-day wages. They’re making thirty bucks a month. In the midst of the Depression, the chance to be able to support your family was huge.

In Chicago, you have up to about half the employable African American population out of work. People are literally going hungry. They’re being evicted from their homes. You have people sleeping in the parks in Chicago. There’s a PBS documentary about the CCC, and you see that many enrollees look back fondly on the Corps because you’re getting three meals a day, clothes, new shoes. All of that is beneficial.

And many enrollees liked the labor outdoors. I would imagine just as many probably didn’t like it, no different than any population doing hard manual labor outdoors in all the elements.

The wages, the food, the clothes, and you’re helping out your family and getting job training. The training white enrollees received, based on my research, is generally better. There were more opportunities for advancement in the CCC for white enrollees. But, for all enrollees, there were classes you could take after your day in the field. There were also sports the CCC, promoted to boost morale.

There definitely were some positive aspects of the CCC. However, some of my work focuses on thinking about the ramifications of how the CCC was segregated, even in the North. In this period, we have white officers who are commanding segregated CCC companies. And while several sources, including the Chicago Defender, the biggest black newspaper in the country, say the segregated African American camps near Chicago were some of the best in the country, a lot of black Chicagoans and other black Illinois residents are going to camps in downstate Illinois or elsewhere in the Midwest, where white officers are frequently, and I think rightfully, accused of racial bias and racial intimidation.

So, getting back to the Great Migration, there is this real tension between how moving to places like Chicago gave African Americans a way to assert themselves and find a greater measure of equality than they were able to find in the South. And oftentimes with the CCC, you have these white officers who are treating black enrollees as if they were sharecroppers. The tension is in the feeling that these young men, these products of the Great Migration, have taken a step backwards by enrolling in the CCC, despite all the benefits.

What do you feel is the legacy of the CCC for African American enrollees?

I think it does, at least temporarily, lead to an increased connection to nature. However, after WWII, you have an even greater wave of migrants to cities like Chicago. This second migration really dwarfs the first wave and leads to intensified segregation and a further restriction of opportunities for African Americans in urban centers to really connect to nature. So, I think there’s this window in the 30’s when African American enrollees – and there’s roughly a quarter of a million nationwide – who are connecting to nature, and I think hold that with them for the rest of their lives. But, the material reality of what comes after this period is the creation of barriers to maintaining that connection to nature.

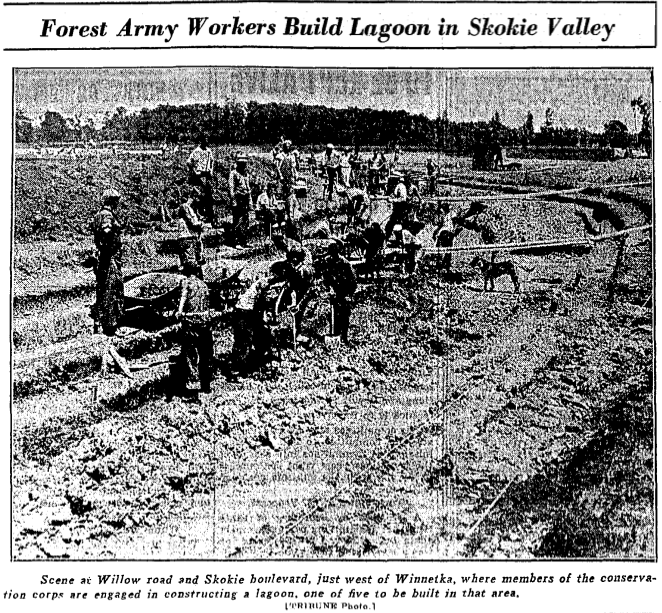

The biggest CCC project I write about is north of Chicago – building what’s called the Skokie Lagoons – taking all this marshland and basically digging it out and trying to create lakes connected by channels so there’s flood control and you can develop the land around it. This space also becomes a leisure retreat for those who live nearby. The sad reality is that this is on the far North Side of the city, which is almost entirely white. This is the kind of segregation that I’m talking about, that pretty much restricts African Americans to the South Side of the city, far from all these places where enrollees worked. The products of their labor are actually enjoyed by middle class whites.

For enrollees, I think the story is one of personal connection to nature during that period when they’re in the CCC, but there are these broader structural forces that, once these enrollees exit the program, really prevent them from maintaining those connections. Even if they’d enjoyed their time in the CCC, even if they found it productive from the standpoint of connecting to nature, it becomes harder and harder to do that in the post-WWII era.

As far as job opportunities, you can’t discount the training in the CCC and the way it helped African American enrollees learn skills they could actually apply. However, it’s also worth noting that African Americans were likely to stay in the CCC longer. They’d stay for six months, then re-up for another six months, or even stay longer. Especially during the Depression, it was harder for them to find jobs due to racial discrimination. Last hired, first fired. Even when the economy starts picking up in the late ‘30s, the white working class is the first to benefit. The African American working class – the kinds of young men that are in the Civilian Conservation Corps – really don’t see the fruits of that until industrial production ramps up with WWII.

Can you talk about green spaces that African Americans sought out or created for themselves as they moved North? For those who settled in cities, what were the opportunities to get outdoors?

I think one of the biggest reasons connecting with green spaces was so important for migrants was because it was intertwined with connections to Southern folk culture. Being able to connect with the environment is a way to connect with the rural lifestyle you left behind. A lot of migrants didn’t necessarily want to leave the South; they were essentially forced to leave because of the racially oppressive and violent policies afflicted upon them.

The sad story is that they find racial oppression in the North, it’s just different. The majority of migrants in the Great Migration aren’t living in suburban environments. They are, by and large, restricted to the more cramped, rundown and unsanitary portions of the city. So, if they’re connecting to green spaces, chances are it wasn’t privately owned green spaces. Most of the working-class migrants coming to Chicago don’t have a yard, don’t have room or time to cultivate a garden. There certainly were black Chicagoans who did that, but I think that was more of an exception. So, if they’re seeking aspects of nature, they’re doing so in public spaces. They’re becoming modern urban dwellers, seeking out green spaces just like every other working class modern urban dweller seeks out nature in city parks, in the beaches, in the forest preserves around the city. And, if you have little bit more money, going on vacation at a rural resort.

A lot of black Chicagoans, especially those who were more well-off, went to resorts. The most well-known one that I write about is in Idlewild, MI. Several hours away from the city, a self-segregated African American resort colony springs up, and this is only the most notable of them. This is happening all over the country on various scales.

The predominant story, however, is that these urban dwellers would, maybe on a Sunday – the one day off they have each week – go with their family and friends to a city park and just hang out. One of the things I write about is playing music – ukuleles and things like that – on the tennis courts in Washington Park, a massive 371-acre Frederick Law Olmstead-designed park that’s built in the late 19th century, when African Americans didn’t live anywhere near it. But as the “black belt” on the south side of Chicago expands further, it ends up abutting this huge park. By the 1930s, it becomes a de-facto black park.

So Chicago’s parks were at least informally segregated?

Yes, I think that would be the best way to put it. “De-facto segregated.” There weren’t necessarily signs posted. However, to give you an example, look at Jackson Park Beach on the South Side of the city. African Americans began using the lakefront and continued to push south as the black belt expanded. They’re going to beaches that are closest to where they live and work. Well, the white folks who lived in Hyde Park and elsewhere and were using Jackson Park Beach – and there’s no official explanation for how this came to be – but there was a fence erected on the north end of Jackson Park Beach and it was just generally known that African Americans were only to use the north end of that beach and whites reserved the longer, sandier, better portion of the beach for themselves. If an African American ventured to the southern portion of the beach, they were risking violence. This is how the race riot started in the city in 1919. A young African American boy – 17 years old – unwittingly floats too far south into what whites were trying to protect as a whites-only beach. A stone is thrown at him and he drowns, and it touches off this race riot.

So yes, parks were not officially segregated, but, if you were to interview folks who grew up in Chicago in the ‘30s and ‘40s, they’ll say you just knew you couldn’t go to the white recreation areas. And that line keeps shifting over time. Washington Park was a white park up to the 1920s. Then there’s this decade of transition and, by the ‘30s, whites basically abandon their use of Washington Park.

One thing we want to examine is why the environmental movement looks how it does today. Why has it lacked diversity? From your perspective, do you see any historical context for why the conservation movement and our land management agencies are predominantly white?

That’s sort of my next project, actually. Figuring out how environmentalism stayed white is basically the argument of my second book – it’s still in its infancy.

I think there are a lot of reasons. The Civilian Conservation Corps gives you one indication. I think a lot of white enrollees look back fondly on their time in the CCC, and I think that’s true for many black enrollees, but that vastly different labor context that we talked about taints that connection to the environment.

In the period right after the Civilian Conservation Corps, you have mass suburbanization, white flight from city centers, and hundreds of thousands of additional African American migrants pouring into city centers. Opportunities to connect to nature, whether you’re talking about city parks or forest preserves, or even the wilder spaces where CCC companies worked, they become more restricted because of suburbanization and these structural barriers that are erected in the post-WWII era.

If you look at the decade after that, when the environmental movement is coming about in the ‘60s and ‘70s, it’s mainly a middle class white movement. One thing I’ve talked about and written about before is the Black Panthers talking about environmental justice issues: pollution in the cities, inadequate garbage removal, disease, and other issues that afflict their communities in the ‘60s. They’re talking about stuff that the Clean Air Act helps resolve. However, by the time you get all that legislation on the books in the early ‘70s and the environmental movement becomes institutionalized and more of a lobbying and litigation movement rather than a grassroots movement, it begins to wholeheartedly ignore African Americans and issues that concern people of color in favor of promoting rural and wild spaces.

And that’s how you get the environmental justice movement springing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s. You have people of color saying the environmental movement and conservationists are not representing our interests. And it’s only in the past decade or two that I think environmental groups have made a conscious effort to diversify their ranks, to address issues that matter to people of color, to get more people of color into the national parks. There’s still a long, long way to go.

The story I tell about the 1920s and ‘30s is the beginning of institutional barriers that prevent African Americans and other people of color from accessing nature. The barriers that come up in that post-WWII era dwarf the ones I write about in the 1920s and ‘30s. This is a story of mass suburbanization, redlining, residential segregation, disinvestment in communities of color and the lack of opportunities afforded them. All of that has an impact on the ability of African American families to maintain connections to nature. I think we’re still dealing with that legacy today.

Can you elaborate on what some of those barriers were that came up in post-WWII era that would’ve separated African Americans further from opportunities to enjoy green spaces?

The vast majority of African Americans who migrate to places like Chicago settle in city centers and the white tax base flees in droves. You have massive disinvestment in cities in this post-WWII era, and that has a tangible effect on places like Washington Park. Just walking into Washington Park, you can tell it doesn’t receive the kind of maintenance it needs. This is something I touch on briefly in the epilogue of my book, but all of those social problems that come along with disinvestments in communities – drugs, violence, gangs – that’s not confined just to city streets. That spills into park spaces and makes them uninviting places to go. All the issues that afflict black communities during what historians call the “urban crisis” in the ‘60s and ‘70s – that has a tangible impact on the experience of green spaces in the city. Parks became places that weren’t safe to let your kids run around.

The same sort of thing happens in a place like Idlewild, which was a retreat for middle and upper class African Americans. With the collapse of formal segregation barriers in many places in the post-WWII era, African Americans have no reason to maintain their own segregated resort any more. So you see a disinvestment in Idlewild. The resort is sort of in a remote, not exactly picturesque part of Michigan. If you could be on a nicer lake, or right on the coast of Lake Michigan, why wouldn’t you want to be there? However, this place where African Americans had traditionally connected with nature disappears. So that’s just one example of a way that African Americans’ connections with nature are severed in the post-WWII era.

For your consideration:

- To this day, people of color are underrepresented among visitors to parks and other green spaces. What steps can be taken to make parks more accessible and inclusive?

- In your community, do you see any “de facto segregation” of parks or other outdoor spaces?

- If yes, what are some reasons this might be happening? Is this de facto segregation problematic and, if so, what steps can be taken to integrate outdoor spaces?

- If no, in what ways do you believe outdoor spaces in your community have been able to maintain visitation and use by diverse populations?

- During our intervirew, Dr. McCammack discussed how there was tension among Chicagoans about the “proper” way to utilize green spaces. Some people looked down on new comers to the city who used the park for Southern folk traditions, like outdoor baptisms. In your experience, have you seen tension among different park visitors? Do you believe these tensions ever fall along racial, ethnic, or class lines? Have you ever been made to feel like you were using an outdoor space “improperly”?

- Dr. McCammack discusses how one reason why the mainstream environmental movement has remained predominantly white is because the movement has traditionally ignored issues that are relevant to communities of color. What environmental issues concern you most? Do you feel like these issues get adequate attention? What are some reasons why these issues may or may not receive attention?

- For Corps: Do you make it a priority to engage in green spaces that can be enjoyed by all members of a community? Do your Corpsmembers serve in spaces that they can readily access during their free time? Would your Corpsmembers feel comfortable recreating in all the spaces where they serve?